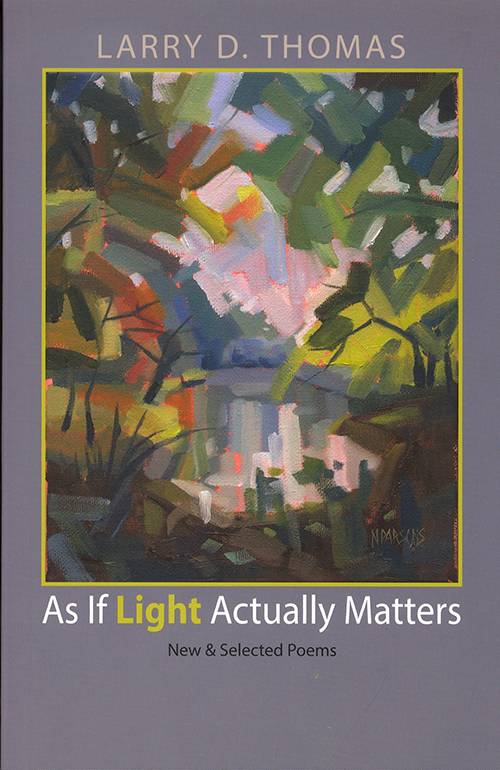

As If Light Actually Matters:

New & Selected Poems

by Larry D. Thomas

Huntsville: Texas Review Press, 2015

200 pp. $12.95 paper

Review Essay by

Sarah Cortez

"The true gift of “selected” work is the poet’s presentation of an intimate peek into his current assessment of his career. In looking at the poet’s choice of poems, one senses that the obdurate sinews pulling the poet’s work forward haven’t changed."

As if Light Actually Matters: New & Selected Poems provides a canvas on which Thomas paints his new poetry with exquisite craftsmanship, far-reaching diction, and a honed ear attuned to the aural treasures of every syllable. The volume begins with a set of forty new poems, in what feels like a manner calculated to ease the reader familiar with Thomas’s decades-long work. There are two poems about people molded by the harsh realities of far West Texas, the primary region of Thomas’s work. In the first of the poems, “Chiaroscuro,” Thomas makes sure we’re hiking his favorite path alongside him as the sections explore first brightness, then blackness.

After this brief reminder of the poet’s preoccupations, he brings us to a location more intimate than the bedroom—the writing desk. As soon as the reader acquires a brief toehold of understanding and observes the poet writing on “a stationery of light,” the reader is whisked into the poet’s musing about the West Texas wind. The reader is immediately removed to another region of Texas in “Deep Woods” and “Lye Soap” before Thomas gives us the dazzling “Winter Trees,” where he fully integrates his figurative ability and sensory memory to create the certitude of brilliant vision.

As the section continues, the poet places before us the smallest creatures: the fly and the translucent gecko. The poet let’s us consider the vastness of their secrets. Then the mood shifts into the eerie stealth of nocturnal predators: the bobcat and the wolf. Their details become art as Thomas seamlessly constructs both myth and beast into one living, lethal animal.

These two creatures that transverse the elements function as a bridge into four poems dealing with creatures, human and otherwise, controlled by fate. From lowing, pasture-bound steers already marked for market to the eponymous “man” cursed by a curandero in the hills, all are defined by destiny.

There follows a series of nine poems—a glowing array—evoking and honoring those humans who chart mysterious topographies. This set of poems begins with “Sleepwalker” and ends with “Our Lady of Guadalupe” and the penitent for whom “The weight of a history/scrawled in rivers/of human blood/has creased her face/into folds of fleshed bronze.”

Never a poet to demur from tackling difficult topics, Thomas delivers some of his most subtle and powerful new work. In his characteristically shortened, enjambed lines, the poet brings us into the darkness and the possibility of oblivion by deploying his obsessively beautiful metaphorical vocabulary honed by years of deft use and deep thought. Thus, images of beauty become images of death; death is found everywhere in this section—the death of vision (blindness), the death of cells (cancer), the death of a wife (loneliness), and the death of military comrades (war).

This section also contains a poem, “Dark Horse,” that holds what is, for Thomas, an unusually ambiguous series of images. Written in first person, the poem allows the poet’s persona, an unnamed companion, and a black horse (“the beast”) to rove the heavens in a manner worthy of William Blake, “quaking the black night / with beautiful thunder” as all three hearts beat “with numinous song.”

“Dark Horse” feels most closely aligned to the poet’s relationship to poesis. The ecstatic union, the inexplicable creation of beauty in the midst of palpable darkness, the reaching out by the poem’s narrator to the companion he cannot see—just as a poet must always be reaching toward the unnamed reader—all these elements are convincing of the poem’s potential to answer the virtually eternal questions any poet must ask himself: why do I write poetry? In fact, not just “why?” but “how?” and “in the face of what odds?” and “at what price?” This is our glimpse of Thomas at his writing desk in a manner much different from the beginning of this section.

This poem also clearly establishes the poet’s triumph over the “black beast / I have straddled bareback.” Yet it is a triumph that allows the blackness to still breathe, and the black beast to continue to split the heavens with its hooves while carrying poet and reader aloft.

The final set of new poems treats light manifested in different circumstances—not a surprising finish considering the book’s title (As If Light Actually Matters) and the title of Thomas’s 2010 book, The Skin of Light. We are invited to consider anew the tragedy of Hart Crane in “His Hard Art” as “he stumbled upon the bones // of Lucifer, the Angel of Light. / It drowned him like a thrashing kitten / in the black well of consciousness.” All of the poems in this set are replete with glimmer, glister, and the dazzle of light, visual art, and music so bright that they can kill the viewer. Yet for some, they simply breathe in companionable silence—for the museum security guard, the pueblo natives, the “five black women,” and (one assumes) for the poet. The only two new poems that appear discordant are “Rudyard’s Pub” and “Even the Roses Are Ill”—minor lapses in the overall tone and mood of the complete section.

The true gift of “selected” work is the poet’s presentation of an intimate peek into his current assessment of his career. In looking at the poet’s choice of poems, one senses that the obdurate sinews pulling the poet’s work forward haven’t changed. They are the careful balancing and simultaneous awareness of light and darkness. The first is blinding; the second is fierce and palpable. Thomas’s repeated approach to the potential for stark terror and/or ecstasy when encountering the ultimate light (the Divine) or absolute evil (the Dark One) is one of the strongest unifying themes of his complete oeuvre. Perhaps these potentials are precisely what originally drew Thomas (consciously or unconsciously, in poesis both function the same) to the far West Texas geography, whose remoteness and harsh realities he has chronicled and for which he has received many prizes.

To Thomas’s credit, the demanding landscape and his personal history with it have drawn forth diction and imagery for rendering it with painstaking accuracy and unsurpassed power. Richard Hugo in The Triggering Town says that a serious poet’s need “to assume ownership of a town or a world is essential.” Thomas owns far West Texas.

One of the fascinating aspects of Thomas’s career is his decision to craft sixteen chapbooks in addition to his nine books of poetry. In some cases, these smaller books are also filled with linotypes or woodcuts created as companion pieces for the poems. Thomas re-affirms the importance of this choice by his decision to include the entire twelve-poem series from the chapbook The Red Candlelit Darkness (2011). This beautiful, albeit ominous and terror-filled, series examines the early 1900s Chisos Mining Company in Terlingua, Texas, from a fictional mineworker’s perspective. Thomas explores his character’s yearnings, fears, nightmares, and the ultimate, tormented death against a panorama of darkness which brings no relief from the killing dazzle of sunshine and sweat. Uncompromising beauty in the face of uncompromising death—trademark Thomas at his best.

Would Thomas and his lock-grip vision be at home in Emily Dickinson’s famous “White Heat?” You bet ’cha—as is said in West Texas. Just as Emily, another plier of the ecstatic and the darkness, would be at home in Thomas’s “red, candlelit darkness.”

In moving from Thomas’s As If Light Actually Matters to Laurie Ann Guerrero’s A Crown for Gumecindo, there are the predicable differences when comparing a poet at the fullness of nuanced control of language and imagery and a newer poet’s wrestling to birth a high-profile project after a full-length award-winning debut.

Sarah Cortez is a Councilor of the Texas Institute of Letters and winner of the PEN Texas Literary Award in Poetry. She is an award-winning anthologist and writer with hundreds of publications worldwide. Her latest anthology is Goodbye, Mexico: Poems of Remembrance (Texas Review Press, 2015), already an award-winning book.