The Pursuit of Happiness

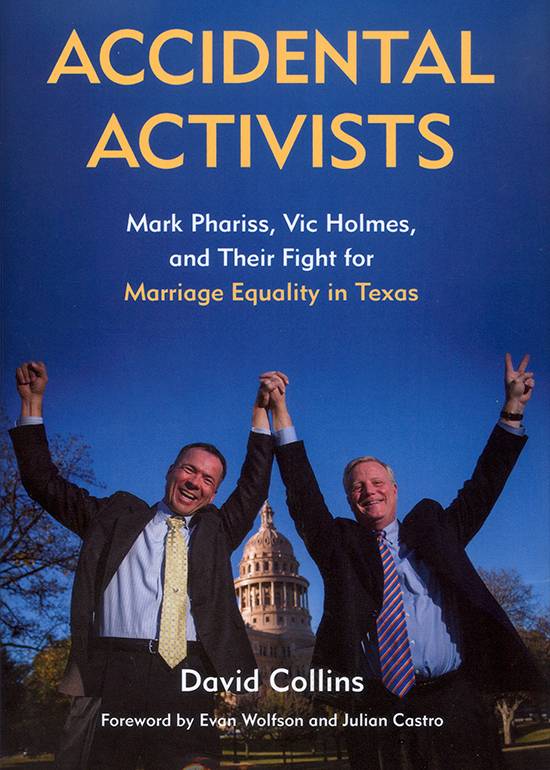

Accidental Activists:

Mark Phariss, Vic Holmes, and Their Fight for Marriage Equality in Texas

by David Collins

Denton: University of North Texas Press, 2017.

394 pp. $29.95 cloth.

Reviewed by

Ulf Zimmermann

"Collins’s account is richly detailed and he shows his readers that Mark and Vic are just like everybody else and deserve the same right not to have their personhood denied because of their 'difference.'”

We know how Mark Pharris and Vic Holmes’s “fight for marriage equality in Texas” ended: On June 26, 2015 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in their favor in Obergefell v. Hodges. Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote, “The Constitution promises liberty to all within its reach, a liberty that includes certain specific rights that allow persons, within a lawful realm, to define and express their identity,” adding, “these liberties extend to certain personal choices central to individual dignity and autonomy, including intimate choices that define personal identity and beliefs.” He concluded, “The right to marry is a fundamental right inherent in the liberty of the person, and under the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment couples of the same sex may not be deprived of that right and that liberty.”

But their win came only after a torturous struggle. Let’s look at some highlights. Obergefell had been argued by Mary Bonauto who had amassed a string of such victories, beginning with “civil union” in Vermont in 1997 and marriage equality proper in Massachusetts in 2001, the first state to so rule. Barney Frank called her “our Thurgood Marshall.”

Mark and Vic’s legal fight began October 2013 when they entered the Bexar County courthouse (they had met and begun their life together in San Antonio) to “mess with Texas” by applying for a marriage license. Being refused was the formality required to file suit. By this time, and long before, they had not really been “accidental activists.” Now in his early fifties, Mark, a successful corporate lawyer, had been publicly engaged in the Human Rights Campaign and he and Vic came to the courthouse accompanied by a lawyer from Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld, one of the foremost law firms of its kind in the U.S. (with Texas origins) who was confident this refusal was unconstitutional—and just the thing for the firm’s pro bono work. Public sentiment had been steadily shifting (Ellen DeGeneres had come out on her show and in life, featured on the cover of Time in 1997; Will & Grace had begun the first season of its long run in 1998; and much of the business community had begun to engage with this “market segment”) and gay marriage bans were falling, domino-like, in courts across the states.

These factors had been preceded by the first of Kennedy’s landmark decisions on gay rights in Romer v. Evans, writing that there was no rational basis on which a state could identify “persons by a single trait and then deny them protections across the board” in 1996, the year before Mark and Vic met. Then there had been his decision in Lawrence v. Texas that decriminalized sexual behavior between consenting adults of the same sex in 2003—and a raft of others.

To make their case complete (both permitting same-sex marriage in Texas and having the state recognize marriages in other states) Akin Gump recruited Cleopatra DeLeon and Nicole Dimetman, a Texas couple whose Massachusetts marriage was not recognized by the state of Texas. Filed in San Antonio, The Federal District Court for the Western District of Texas assigned the case to Judge Orlando Garcia. With such cases now truly cascading across the country, Garcia made it a point to let the arguments for marriage equality be laid out at length and shortly granted their motion a stay (a preliminary injunction against the state). From there it would go to the Fifth Circuit Court in New Orleans, though not until January 2015. But that January they also learned that the Supreme Court would hear an appeal from the Sixth Circuit Court, consolidating cases from four other states—after thirty-five states and the District of Columbia had already legalized such marriages.

Despite the fact that Obergefell was a “retroactive recognition case,” Texas tried to object, with Governor Abbott (something of a friend of Mark’s at Vanderbilt law school) anachronistically [unsurprisingly?] invoking states’ rights. Instead, the state had to pay Akin Gump legal fees. And as in all happy endings, Mark and Vic finally had their big wedding.

Collins’s account is richly detailed and he shows his readers that Mark and Vic are just like everybody else and deserve the same right not to have their personhood denied because of their “difference.” Growing up in Oklahoma, Mark felt the full brunt of this when former Miss Oklahoma Anita Bryant, the forgotten singer, sought a new spotlight organizing hate campaigns against gays and lesbians. Vic meanwhile had served over twenty years in the Air Force, where he could get dishonorably discharged for “sexual misconduct.” He’d eventually become a physician assistant and was now teaching at the University of North Texas Health Science Center.

The book’s origin story is worth noting. Collins was teaching at Westminster College in Missouri when Mark was his student in that universally required English class in the fall of 1978. He was the sort of student teachers remember and they kept in touch. When Mark told Collins that they’d filed suit, Collins said he’d have a great book if he would “write it all down.” Minutes later Mark called him, “Why don’t you write the book?” Just retired, Collins had the time and he has done us a fine service tracing the legal evolution of marriage equality and Mark and Vic’s long personal journey to it.

Ulf Zimmermann grew up in San Antonio, got a Ph.D. in Austin, taught in Houston, and now lives in suburban Atlanta.