Touched For the Very First Time

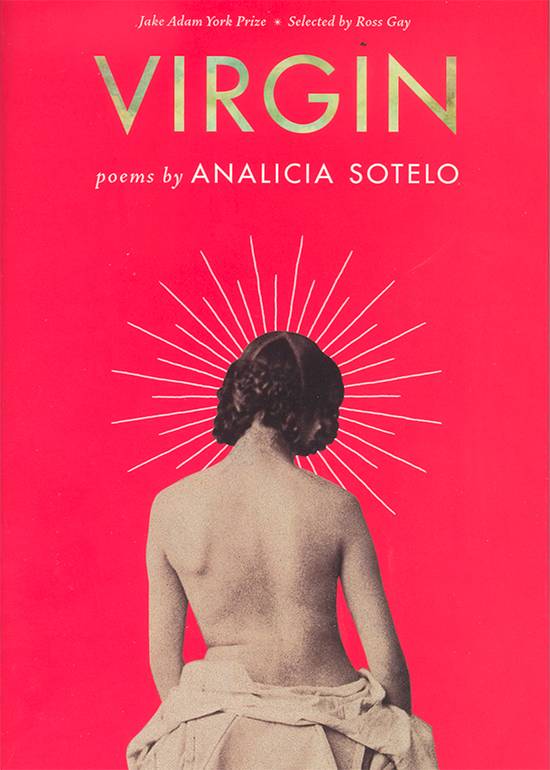

Virgin

By Analicia Sotelo

Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2018.

95 pp. $16 paper.

Reviewed by

Claudia D. Cardona

In Analicia Sotelo’s debut collection, Virgin, she weaves southwestern imagery along with the sensual and nostalgic. Her poetry creates a conversation between Christianity, Greek mythology, and Texas folklore. The first poem, “Do You Speak Virgin?” sets up the scene of a South Texas wedding with stark images like “a bouquet of cacti wilting in my head” and “My veil is fried tongue & chicken wire, hanging off to one side.” Sotelo re-appropriates the Christian idea of the virgin into one that is unabashed, and even outspoken. In the second section of “Do You Speak Virgin?”, the speaker illustrates the power within the virgin:

The virgins are here to prove a point. / The virgins are here to tell you to fuck off.

and again with the last four stanzas of the poem:

Before I sign off on arguments

In the kitchen & the sight of him / fleeing to the car

once he sees how far & wide,

how dark & deep

this frigid female mind can go.

Throughout Virgin, Sotelo illustrates just how dark and deep the speaker’s mind can go. In the first of seven sections, Sotelo traverses through scenes from a summer barbeque, to healing heartbreak in bed, to a Grecian fantasy. Readers are never sure where Sotelo is going to lead them, but it’s always somewhere unusual and haunting. For example, “You Really Killed That ‘80s Love Song” begins with the speaker witnessing an ex-lover kiss someone else on a wrought iron balcony, but the poem ends with the haunting image of the speaker in bed, reflecting on her humiliation, describing it as “the crown-like stigmata of a peach / that’s been twisted, pulled open, left there” and imagining a knife piercing both his and her body.

Sotelo’s poetry is full of regal and lyrical imagery that is infused with the Southwest. It’s as if the poetics of Virgin are housed in a Grecian museum, full of ancient marble statues but also mixed in with southwestern textiles, and ’80s New Wave tracks play on a loop. She locates popular Greek myths within the context of Texas like in the poem, “South Texas Persephone” in her second section, “Revelation.” The speaker imagines herself as Persephone and her lover as Pluto, in a stunning reimagining,

Look now: my heart

is a fist of barbed wire. His heart

is a lake where young geese

go missing, show up bloody

after midnight. I don’t say

a single thing.

Sotelo’s strength as a poet is felt in her pacing and potent use of image. Her short lines and use of line breaks hold the reader in suspension and draws more attention to every word, for example with the line break, “Look now: my heart / is a fist of barbed wire.”

Greek mythology has historically been popular with female poets, ranging from Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Natalie Diaz. With such a broad poetic history tied to Greek mythology, the stakes for writing within this tradition are high. Sotelo succeeds in her portrayal of Greek mythology because she also calls in a variety of other voices. She dedicates two separate sections (Pastoral and Parable) to her father and mother, and abundantly explores the speaker’s traumas, high school experiences, and romantic endeavors. In Virgin, Greek mythology serves as a mirror that Sotelo gazes into, and then shatters.

In another section, Sotelo rewrites the myth of Ariadne and Theseus through a series of poems that are conversation with each other. In the poem “Ariadne’s Guide to Getting a Man,” the speaker begins with a list, informed by the title, but then turns to self-awareness: “The book you are reading is about a girl who rejects a god / The book you are reading is about a girl no one believes” and ends with the mention of Minos and Ariadne, “Your brother is howling / because your mother chose love and look where it left her.” By the time one finishes a Sotelo poem, the connotations of Greek mythology are almost wholly forgotten; one trusts Sotelo to paint an entirely new picture of these myths.

Virgin is also interested in exploring the wounds of heartbreak, particularly heartbreak in the Mexican female body. In “Trauma with White Agnostic Male,” Sotelo illustrates the scene of meeting a white lover at Fiesta at the King William District:

You’ll mock a trio of mariachis,

a cer-vay-sa in your spidery hand.

That’s how you’ll say it: Sir Vésa

for love of my tender Latina outrage.

Sotelo explores this theme until the end of the collection. One of the last poems of Virgin, “My English Victorian Dating Troubles,” outlines how the speaker navigates her dating life with lines like,

Why does the twenty-first century feel like this?

Like men are talking into

their favorite phonograph

& their phonograph is me

Receiving their baritone: You’re so exotic

Watch out, men, says my violin

I am a Royal Bengal man-eating tiger

I will devour your pith helmets

as well as these enchiladas

piled high with American mozzarella any time of day

In response to men fetishizing the female Mexican body, Sotelo posits the speaker’s body as dangerous and ravenous with her excellent mention of enchiladas. Her humor cuts through her stark descriptions and observations on romantic love.

Project poetry books can either be extremely successful (Tyehimba Jess’s Olio) or they can fall flat. Sotelo transcends the conceptual project and rather threads Greek imagery and mythology, trailing out of the territory into a space that is otherworldly, tragic, and very San Antonian. Virgin is a constellation of Sotelo’s own mythology, heartbreak, family, womanhood, and faith—a constellation so bright and shiny that one never wants to lose sight of it.

Claudia D. Cardona is the editorial fellow for the Center for the Study of the Southwest. She is currently a poetry candidate in the MFA program at Texas State University. Claudia is also the Editor-in-Chief and Co-Founder of Chifladazine, an online and print publication that is dedicated to showcasing the creative work of Latinas and Latinxs.