The Rise of Chuco Punk

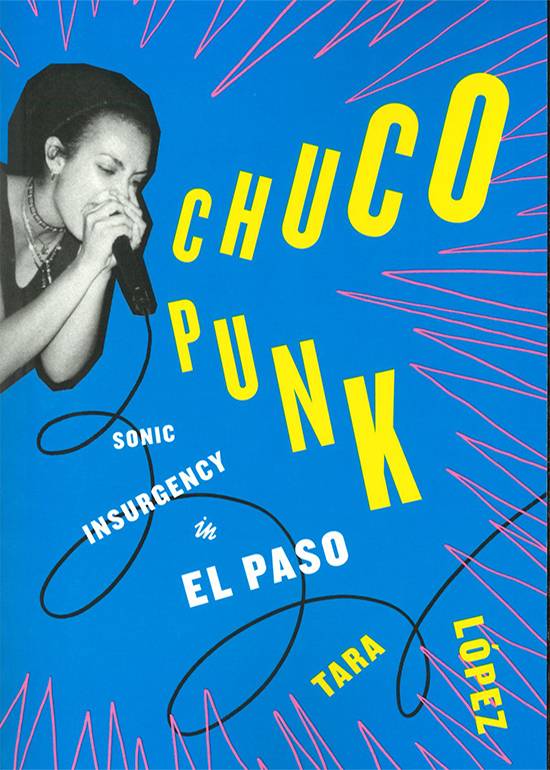

Chuco Punk: Sonic Insurgency in El Paso

by Tara López.

Austin: University of Texas Press, 2024.

208 pp. $21.95 Paperback.

Reviewed by

Hannah Martin

Tara López starts Chuco Punk: Sonic Insurgency in El Paso with a story that sums up the “do it yourself” spirit behind punk music. To celebrate the new release from Jerk, band member Sergio Mendoza had a backyard show at his house where his mother, Isabel Valenzuela Mendoza, served nachos and burritos. When there’s no venue to accommodate your show, punk allows you to make one. And when the cops intrude, it's nice to have a punk rock mom to hide the earnings of the night in a ceiling tile. Through over seventy oral interviews, flyers, and photos, López tells the history of El Paso through the lens of its punk resistance from the late 1970s to the early 2000s. Her emphasis on Chicano/a punks sets her apart from other scholarship that focuses on white, male musicians. She argues that punk was never a white man’s genre and sheds a light on Chicano/a’s continued resilience in El Paso during times of change, hardship, and discrimination.

López breaks up the book into four parts. First, she sets the scene of El Paso and Chuco. The word Chuco, as López writes, comes from the Spanish word for “crooked” or “illegal.” It was used to describe El Paso as a place of subversion, sin, and criminals. The punks of El Paso then take back the word “Chuco” as a sense of their Chicano pride. López first takes readers back to the 1890s to discuss the changing demographics in El Paso, when Anglo Americans started discriminating against the Indigenous and Mexican population. From vagrancy ordinances to the Ku Klux Klan, tension between Mexicans and Anglos grew fast. López argues that Corridos were the punk rock of that era, because they were made by and for ordinary people and often had protest undertones. This argument is accurate if the definition of punk leans more towards ideology than sound. López also does a good job of educating readers on the complexity of El Paso being a borderland between Texas and Mexico. She does not shy away from discussing punk gangs and their rivalries to establish their own identities within Chuco.

The next two parts are the bulk of the book where it dives into the first two generations of punk. López describes the first generation as setting things up for the second through backyard shows, punk gangs, radio shows, and skate parks. For the second generation, López writes more about the nuances of backyard shows with the Arborela House and the politics behind punk through organizations such as La Mujer Obera. This is also the generation of bands like At The Drive In, that eventually break into the mainstream. The fourth section, notably titled “Indelible Chuco,” dives more into the impact of Chuco punk outside of El Paso. This is where female punks get more recognition, especially in the fight against the femicides that occurred along the border in the late ’90s. López concludes with Chuco punk’s larger legacy. For López, Chuco punk provides a great example that the punk genre is made for people of color. For those who were involved, the memory that sticks around the most was the scene’s sense of community.

López excels at bringing female punks to the forefront. This is one of the highlights. The first example of this is Jenny Cisneros as the book cover. Immediately readers will identify Chuco punk as being female led. by defining Chuco punk as more than musicians. Lopéz centers the female fans, managers, zine creators, and mothers like Isabel Valenzuela Mendoza that let shows go on in their own backyard. Her discussion on the Mujer Festival, created to raise awareness on the femicides, is a powerful example of the intersection of punk, politics, and gender. These nuances – complex overlays? — could (and probably should) be another book entirely. What makes this book special is López’s dedication to oral history. Using over seventy interviews, López can intertwine stories with a more academic history of El Paso. She often includes quotes from her interviews that help bring a personal take to the larger story. These punks were real. They deserve to be heard.

Tara López is also punk. Her love for the genre and the people of El Paso is shown throughout the book. Now an assistant professor of ethnic studies at Winona State University, she utilizes her scholarship to give others an insight into her own community. This may mean that the book has an inherent bias, but with her substantial interviews, evidence, and analysis, Lopéz makes it clear that Chuco punk made an impact not only in El Paso but around the world. In her words, Chicanx/Latinx were “not just asking for a seat at the table. They built the damn table too.”

Hannah Martin works at the Wittliff Collections as a metadata specialist, where she focuses on digitizing their Texas music collection. She graduated with a bachelor's in history from St. Edward's University and earned a master's in public history from Texas State University. Her work centers on Texas music, particularly the influential women in Austin's punk scene.