Lights, A Question Of

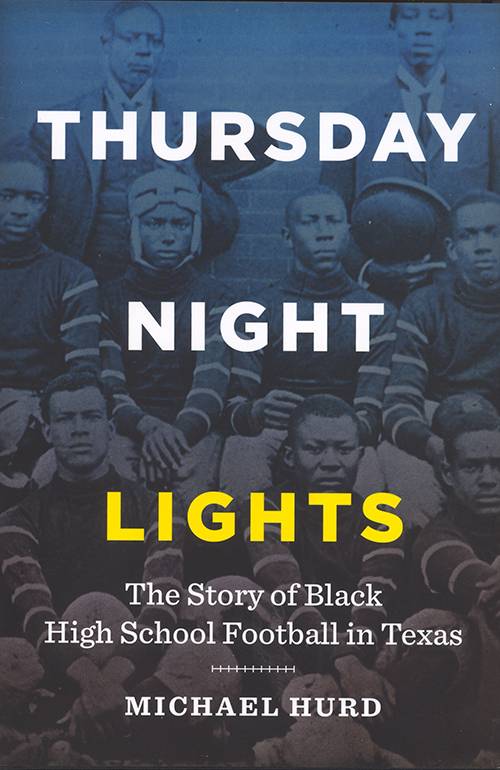

Thursday Night Lights: The Story of Black High School Football in Texas

by Michael Hurd

Austin: University of Texas Press, 2017.

248 pp. $24.95 cloth.

Reviewed by

James Wright

The bright lights of the famed football fields of Texas’s high schools have shined on some of the greatest football players of all time. A quick peek at the last seventy-five years of high school football in Texas reveals some of the finest talent to ever strap on a helmet. The last few decades have given us such gridiron greats as Earl Campbell, Billy Sims, Mike Singletary, Eric Dickerson, Thurman Thomas, Michael Strahan, and Vince Young. The ’50s and ’60s produced a comparable group of stars, including Dick “Night Train” Lane, Charlie Frazier, Charley Taylor, Ken Houston, Charles “Bubba” Smith, “Mean” Joe Greene, and Cliff Branch. While there is no denying that these two groups of players are united by their remarkable skill and legendary status, there is likewise no denying that they are divided by a striking difference, one that had nothing to do with their aptitude for football and everything to do with the color of their skin: the night of the week on which they played, on which they were allowed to play.

On June 9, 1965, the Texas University Interscholastic League (UIL), an organization established by the University of Texas in 1910 to oversee scholastic, musical, and athletic competition for primary and secondary public schools, amended its longstanding segregationist policies and voted unanimously to remove the word “white” from its constitutional restrictions on school and student eligibility, thus extending membership for the first time to “any public school.” This far-reaching change in organizational direction, as Michael Hurd so poignantly documents in his Thursday Night Lights: The Story of Black High School Football in Texas, delivered a bittersweet victory to those schools, and the state organization that presided over them, long disregarded by the UIL. For inasmuch as the UIL’s move toward integration served as a beginning to political recognition for the state’s African American population, it also marked the end to the exceptional and proud legacy of an organization that “showcased some of the best prep-school football talent in the country,” and “[whose] games revived spirits battered by the day-today burdens of racism”: the Prairie View Interscholastic League (PVIL). Despite the fraught dimensions to the UIL’s decision, it was clearly responsible for one notable accomplishment: enabling black prep-schoolers to play, finally—and thrive, unsurprisingly—under the fabled lights of Friday night.

Ritualized in story and practice, Friday night high school football in Texas—mythologized as Friday Night Lights—functions as a long-standing Texan point of pride. In Thursday Night Lights, Michael Hurd reminds us that it also serves as an enduring point of shame. Prior to the 1965 UIL decision (which was not fully implemented until the athletic seasons of 1967-1968) the official segregationist practices of Texas assigned “white schools… priority for the Friday-night use of public stadiums shared with black schools.” Games for black teams were relegated to Wednesday and Thursday nights, a scheduling practice, that as Hurd describes it, “carried a ‘less than’ feel” to it. Determined to “stake a legitimate claim to its own prowess, with programs that featured speed, athleticism, and a taste of showmanship,” black schools and coaches founded the PVIL.

Established out of Texas Interscholastic League of Colored Schools (TILCS) roughly a decade after the founding of the UIL, the PVIL provided governance, in the same manner that the UIL did for white public schools, for scholastic and athletic competition. It was on the football field, though, where the PVIL wrote its story, even if, thanks to the efforts of Hurd and others like him, it is only now being read. For, as Hurd explains it, while the UIL claimed to represent “the prep football capital of the nation,” and while it “was the most organized, most publicized, [and] most funded” public school organization in Texas, it “wasn’t even the most talented football league in its own state.” That title, as Hurd painstakingly details in his book, belonged to the largely neglected PVIL.

Comprised of illuminating interviews with many PVIL figures and careful research of the organization’s history (Hurd did not have the luxury of reviewing game and season statistics, since the league and its member schools felt no compelling need to keep them) Thursday Night Lights provides an absorbing account of the dogged strength and rugged perseverance of black high school football coaches, teams, and players in an era of overwhelming state-sanctioned racism. Motivated by the need to bear witness to the unheralded civic and athletic significance of the PVIL, Hurd, the director of the Texas Institute for the Preservation of History and Culture at Prairie View A&M University, places particular emphasis on the stories of the proud league’s coaches, players, and teams. Hurd pays tribute to treasured coaches such as Joe Washington, who for nearly fifty years at high schools in Bay City and Port Arthur coached a number of great players to successful careers, one of whom became a two-time all-American at the University of Oklahoma in the mid-1970s and was “the fourth player selected in the 1976 NFL draft”—his son, Joe Jr.; to groundbreaking players such as quarterback Eldridge Dickey, who was selected by Al Davis’s Oakland Raiders in the first round of the 1968 NFL draft, making him the first black quarterback to garner such an honor; and to legendary teams such as East Austin’s Anderson High School, who, in perhaps apocryphal fashion, beat the Texas Longhorns in a scrimmage in 1944.

Hurd’s history of the PVIL is a story of ability subordinated to power; of effort foreclosed by exclusion. It is also a story of wherewithal, dignity, and triumph. In a narrow sense it is a story of the African American experience in the racially hostile environs of the segregated South; in a broader sense, of blackness in the history of America. As Hurd is keenly aware, his book, in an act of indirect counterpoint, is also a story of whiteness—for Friday Night Lights, as a best-selling book, as a television series, as a major motion picture, as a symbol for a quintessential Texan way of life, and, of course, as a discriminatory institutional practice for most of the twentieth century, has its basis in whiteness. Part of what Hurd’s history does so admirably is demonstrate how the mythopoeia of Friday Night Lights developed at the expense of a great many of those who made the tale what it is while being absent from, if not written out of, the tale itself. Thursday Night Lights begins the process of reconsidering, and subsequently challenging, the flagrant elisions of such a tale. And in stating that “the grandsons descended from PVIL athletes are now celebrated for their play at UIL schools,” Hurd is not only pointing out a sad irony of the history of segregated football in Texas, he is also gesturing toward the pendulum-shifting energy produced by those who made up the PVIL.

James Wright is Houston regional editor for Texas Books in Review. He teaches composition and literature at Houston Community College.