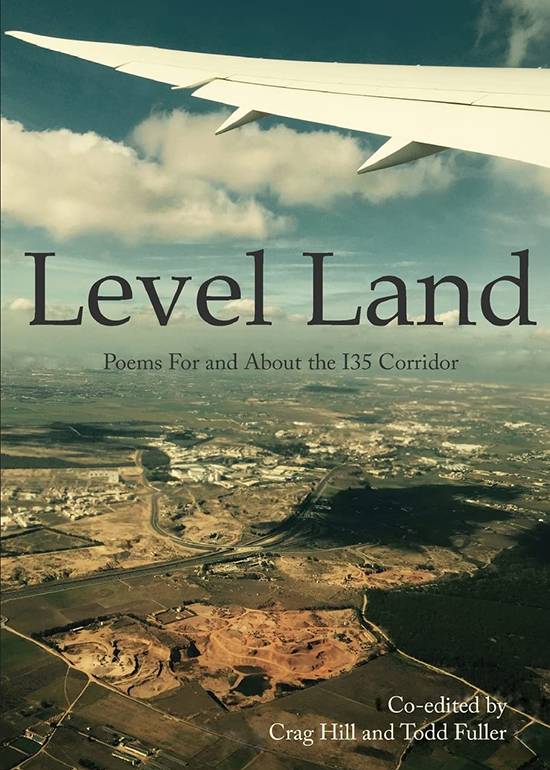

Level Land:

Poems For and About the I35 Corridor

edited by Crag Hill and Todd Fuller

Beaumont, TX: Lamar University Literary Press, 2022.

271 pp. $25.00 Paperback.

Reviewed by

Joshua Bridgwater Hamilton

“Regardless, the generous offering provides the reader with a multi-faceted, prismatic experience of many lyrical moments that, all taken together, give a sense of identity to the corridor as a shared place.”

Level Land: Poems For and About the I35 Corridor presents a bewildering and diverse array of poems. The editors align the scope of the anthology along the reach of the I-35 corridor within the United States, as well as by its extensions into Mexico and Canada, thus covering most of North America in four sections entitled “Borderlands,” “Cross Timbers,” “Tall Grass Prairie,” and “Upper Mississippi.” Much of the lyrical action occurs in the arid reaches of Texas or the tornado-torn expanse of Oklahoma, but the collection includes significant voices from Northern Mexico in Spanish to Indigenous peoples as far north as Canada.

The poems begin in the south and move north, creating a heterogeneous, updated representation of the Great Plains region that informs the reader of the rich set of identities found therein. From Northern Mexico and the border, the reader gets an insightful account of immigrant and borderland experience, then moves through Texas and Oklahoma, where the poems illustrate the cultural context of various heritages in rural and urban areas, and finishes in the stark northern reaches of Minnesota and Ontario, witnessing the impact of geography and weather on all these regions. This volume corrects the image of the Great Plains as an empty area and presents, instead, landscapes and cultures that are best experienced by driving through and experiencing them firsthand.

The section “Borderlands” begins strongly with Andrea Alzati’s poems, both in Spanish and in English translation. The imagery in Alzatí’s poems create oniric landscapes and scenes that resonate with the literary heritage of realismo mágico in writers such as Juan Rulfo: “The city swallowed milk / as it / swallowed any / fluid from any / wound that / was still open / by conviction / or forgetfulness.” While Alzati’s work grounds itself deep within the context and interests of Mexico, subsequent poems focus on the borderlands. Marcelo Hernandez Castillo foregrounds the transition into North American culture in “Immigration Interview with Jay Leno”: “Are you alone? / North was whichever way / the mannequins were pointing. / The softest bone was the one / that burned the longest.” As we advance, the focal point of the poems travels northwards along I-35 and explores the Texas landscape and climate. Kevin Prufer explores the issue of treating overpopulation by hogs with poison in “Hog Kaput”: “So now, driving home / past the fields, now empty of hogs, / with her head beside him... / well, who could be happier / than he was?” Ken Hada’s “Maragritas and Redfish” brings the reader into a more sentimental connection with stories, restaurants, and gas stations from San Antonio to Oklahoma City. More emotional and mythological aspects of the Southwest enter the lyrical conversation in many poems, such as Loretta Diane Walker’s “Offsprings of Extremes,” where “In the cathedral of sky, / Night, with his broad-shouldered / deep-throated darkness, / takes Moon as wife,” tying the personal and emotional together with sensibilities that predate the European immigration.

The second section, “Cross Timbers,” takes the reader further into Texas and on to Oklahoma and Kansas. Lydia Renfro's “Choctaw Ri(gh)tes” presents the confluence of present and past in the speaker: “I'm not full-blooded; diluted one, me, / Ignorant of ancient memories / Shared by my tribe.” The surreal voice in Hala Alyan's “Turnpike // Ghost” contemplates Oklahoma through a train window: “Orchids, purple-furred. Trashed along with the orange peels. / Tulip-wearer. I never understood Brooklyn, // how a place could be bigger than it was.” And the overlapping histories of the region appear in LeAnne Howe and Dean Rader's long poem “The Great Run, Caldwell, Kansas, April 22, 1889”: “Forget wild Indians, / 50,000 Européens Settlers / Will not be stopped / She said. / One day we'll build / A route, / A road, / Carve a deep cut, / Right down the belly of the land.”

“Tall Grass Prairie,” the third section, moves through Kansas with poems that alternate between lyrical contemplations of land and weather and realistic evocations of place and people. Jennifer Boyden's poem “In My Original Kansas, When We Were Iron” ranges from “The Kansas we knew 500 years ago / when we were a wagon wheel” to the contemporary era in which “I had to learn to drive past / neon lights and liquor stores / and to stand upright at parties / without putting my hands / down people's pants.” Denis Low's “Chicory Afternoon” counters Boyden's temporal scope with a poetic examination of the present: “Sky-snatched galaxies burst. // Porcupine is a nimble fat man's shadow. // Greens are seven calories a plateful: / add sugar and vinegar.” The section ends with Gus Palmer's experimental series “Indian Doctor,” “Indian Doctor 2,” and “Augau Sep Gà Âigù (There Goes the Rain),” which combines verses in Kiowa and English.

The anthology concludes with the section “Upper Mississippi,” which takes the reader north to the Canadian border. David Clewell highlights unpredictability in his “Sonata for Tornado in EF-5 (Major): May 22, 2011, 5:41-6:13pm,” detailing the destruction of Joplin, MO. Iowa appears in Ted Kooser's “A Reappearance,” in which a semitrailer is “Settled in nettles and brush by an old barn” where the speaker reencounters a sign he made as an apprentice letterer. Jennifer Boyden's poem “What We Did Instead” observes the intimacy between husband and wife against the backdrop of global war while in Minnesota. The anthology brings the reader back to the intersection of Indigenous and European contexts in poems such as Kimberly Blaeser's “The Ritual of Wishing Hands,” where the speaker wonders, “Perhaps Black Elk's red roads and black converge here / where the tired back of Turtle's earth / and the immense sky world of Thunderbirds / meet in the everyday prayers of tiny hands.”

The editors find a balance between heritages along I-35: the Latinx, the Anglo, and the cultures of the First Nations occupy significant room in this collection. The representation I did not see included African American and Asian American. The anthology offered a spectrum of voices that made it accessible, including work from both established and regional poets, as well as much lesser known writers. If anything, the anthology may reach too far, its 270 pages providing too much content in the endeavor to represent the reaches of I-35. Regardless, the generous offering provides the reader with a multi-faceted, prismatic experience of many lyrical moments that, all taken together, give a sense of identity to the corridor as a shared place.

Joshua Bridgwater Hamilton is a graduate student at Texas State University. He has two chapbooks, Slow Wind and Rain Minnows, and his poetry has appeared in Windward Review, Driftwood, San Antonio Review, and elsewhere.