The Original H-Town Takeover

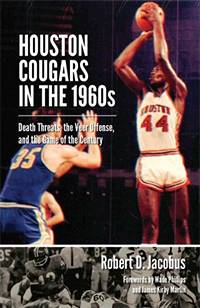

Houston Cougars in the 1960s: Death Threats, the Veer Offense, and the Game of the Century

by Robert D. Jacobus

College Station: Texas A & M University Press, 2015.

392 pp. $29.95 cloth.

Reviewed by

James Wright

On January 12, 2015, Tom Herman, the architect of Ohio State University’s national championship-winning offense, was introduced as the thirteenth football coach of the University of Houston. To be exact, as his official introduction as coach by the University had occurred a month prior, Herman introduced himself: in the confetti-shower afterglow of OSU’s drubbing of the University of Oregon, Herman appeared in a Twitter feed donning a University of Houston cap and flashing the cougar hand-sign. It was the start of a social-media and on-the-field campaign that resulted, in less than a year’s time, in a dominant win against the Florida State Seminoles in the Peach Bowl, a 13-1 record, and a #8 ranking in the final AP poll. Herman called his campaign the H-Town Takeover.

A different kind of H-Town Takeover had taken place at the University of Houston fifty years before Herman’s electrifying arrival. While similar to Herman’s in that out of its local pursuits sprang national implications, the goals of this earlier takeover reached well beyond the field of play. In the spring of 1964, Guy V. Lewis, nearing a decade as the basketball coach at the University of Houston, signed Elvin Hayes and Don Chaney to national letters of intent. A couple of months later, third-year University of Houston football coach Bill Yeoman signed Warren McVea. While their signings inaugurated decades of success for both athletic programs and launched successful collegiate and professional careers for the players themselves, it is the impact that their signings had on the landscape of major college sports in the South that has stood the test of time: as the first African American players in the basketball and football programs at the University of Houston, Hayes, Chaney, and McVea served as trailblazers for the racial integration of major college sports across the South. In Houston Cougars in the 1960s: Death Threats, the Veer Offense, and the Game of the Century, Robert D. Jacobus carefully chronicles the experiences of these three athletes, their teammates, and their coaches as their athletic endeavors became notable steps in the larger campaign for civil rights.

The integration of the University of Houston's athletic programs occurred two years after the integration of its student body. To lessen the fraught politics of the processes, school administrators and coaches, as Jacobus deftly documents, stressed the value of academic and athletic quality over racial politics in the making of both decisions. Philip G. Hoffman, University of Houston president from 1961 to 1977 and the person who oversaw the desegregation of the school, stated that his “‘resolution was to get the best possible students on campus regardless of their color. The later recruiting of black athletes was a byproduct of our integrating the school.” In a meeting with Houston black community leaders in the lead-up to integration, football coach Bill Yeoman offered a similar perspective, albeit with a comedic wink toward the charged nature of the situation. Yeoman said: “I’m prejudiced, all right… I’m prejudiced against bad football players.” Eager to sign black players from the moment he arrived, Guy V. Lewis encouraged many of his recruits to begin their collegiate careers at junior college while waiting for what he forecasted as the inevitable desegregation of University of Houston athletics. In fact, in 1963 Lewis lost out on one of his most prized recruits, David Lattin, whose “dream was to play basketball at the University of Houston,” because of University of Houston’s segregated athletics department. In a twist of fate, Lattin went on to help Texas Western University, and its all-black starting five, win the national championship against the all-white starting five of the University of Kentucky. Yeoman and Lewis would finally get their desired athletes in the fall of 1964 with three incoming players who would chart the direction of University of Houston’s athletics for decades to come while irrevocably altering the racial status quo in the South in the process.

The places of Don Chaney and Elvin Hayes in basketball lore are fairly well known: Chaney was a key contributor to the University of Houston’s back-to-back Final Four appearances in 1967 and 1968 and a successful NBA player and coach for nearly four decades; Hayes, who presided over the University of Houston’s victory against UCLA in the first nationally televised college basketball game, was the National Player of the Year in 1968, a twelve-time NBA All-Star, and a member of the NBA’s fifty greatest players. What is less known about these men is the discrimination they faced in the city of Houston and across the South as forerunners of collegiate desegregation. Jacobus tells, through the nearly 250 interviews he conducted with members of the ’60s-era University of Houston athletics department, of the open racial taunting of visiting black players that occurred at the University of Houston basketball arena before the arrival of Chaney and Hayes, and of sudden rapturous support of on-court racial diversity after their arrival, as the two turned the school’s once-fledgling basketball program into an immediate national contender. Jacobus cites Chaney as suggesting that “‘the timing for integrating UH was great. The school and the students were ready—they wanted a winner.’” And win University of Houston did—with a frequency that set Guy V. Lewis on the road toward his 2007 induction in the Naismith College Basketball Hall of Fame.

Warren McVea, University of Houston’s first black football player, hailed from San Antonio’s Brackenridge High School. Named “the best runner of the 1960s” by Dave Campbell’s Texas Football, McVea had scholarship offers from every major college football program in the country in 1962. To sign McVea, Bill Yeoman solicited the help of local African American community leader Quentin Mease, who thought that landing McVea “would impact the whole collegiate system.” Signing with University of Houston because he was a self-proclaimed “mama’s boy” who wanted to stay close to home, McVea could hardly have imagined the significance his decision, and the many firsts that would arise from it, would end up having on collegiate sports. Some of McVea’s groundbreaking achievements were personal, such as being featured in the first article about a freshman college athlete in the history of Sports Illustrated, running for 128 yards against Washington State University in the first football game to be played on Astroturf, and leading University of Houston to an AP ranking of # 2 in 1967. Others were part of a much larger social transformation, including being the first African American to play against Mississippi State, the University of Miami, and Ole Miss University, a game in which “he caught two long touchdown passes.” McVea was also the first African American to play football at the stadiums of the University of Tennessee, the University of Kentucky, Mississippi State, and Ole Miss, who hanged McVea in effigy at a pep rally before the game. And even though the on-field accomplishments of his college and professional career fell short of those of the other two members of his integration cohort, McVea, as Jacobus so aptly puts it, “changed the course of history in American football. Integration would become the rule and not the exception—a fitting, long-overdue rule of conduct on football fields everywhere in this nation.”

In his Foreword to the book, Wade Phillips, the long-time NFL coach and defensive guru, who arrived to play football at University of Houston a year after Warren McVea, proclaims that “a written history of Bill Yeoman’s pioneering spirit on the University of Houston football field and Guy V. Lewis’s courageous recruitment of Hayes and Chaney for work on the basketball court is long overdue.” With Houston Cougars in the 1960s, Jacobus has commendably provided such a history.

James Wright is Houston regional editor for Texas Books in Review. He teaches composition and literature at Houston Community College