Tough Guy

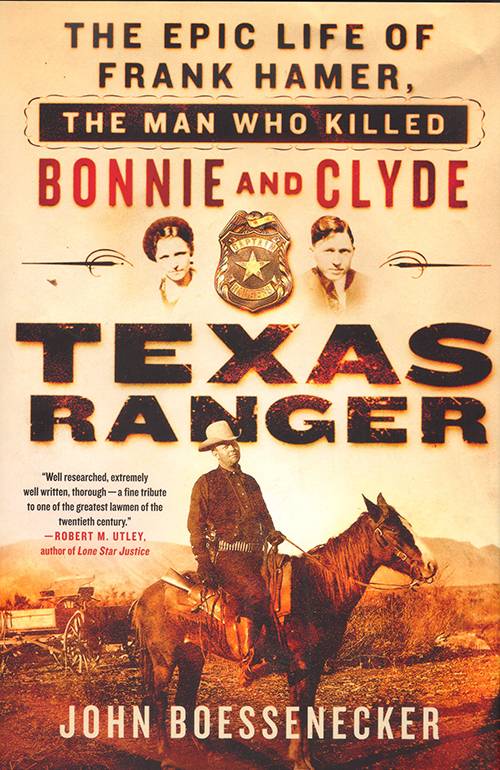

Texas Ranger: The Epic Life of Frank Hamer, The Man Who Killed Bonnie and Clyde

by John Boessenecker

New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2016.

462 pp. $29.99 cloth.

Reviewed by

Joe McDade

Almost every famous outlaw who died by gunfire will be linked, for all of history, with the fellow who laid him low. Billy the Kid had his Pat Garrett, John Dillinger had his Melvin Purvis. Jesse James had Robert Ford. Think of one and you’ll think of the other.

So what of Frank Hamer, the man who brought down Bonnie and Clyde, whose biography is virtually the story of twentieth-century Texas? Why is he not as well known as Wyatt Earp, Elliott Ness, and Wild Bill Hickok? In part, because he shunned publicity. In part, because—astonishingly—the 1968 film Bonnie and Clyde cast Hamer as the villain. For whatever reason, Hamer, who probably had the most impressive career of the bunch, slipped through the cracks and became the lawman that time forgot.

Until now.

Hamer is, yes, the man who, with his modern-day posse, gunned down the most famous outlaw couple in American history. However, in the depth and richness of John Boessnecker's book, Texas Ranger: The Epic Life of Frank Hamer, the Man Who Killed Bonnie and Clyde, we find out so much more. In Texas Ranger, neither Bonnie Parker nor Clyde Barrow receive a single mention until page 387. What comes before is the story of a good, brave man, and a perilous life spent confronting the seedier (and deadlier) elements of race, cattle, oil, sex, politics and the Mexican border—in short, a life spent keeping the peace in Texas.

Hamer was born in 1884 in the Hill Country west of Austin, and he spent most of his boyhood outdoors—camping and hunting and becoming an expert with guns. In 1905, he found his destiny when, while employed as a cowboy in Fort Stockton, he helped the sheriff capture a horse thief. The sheriff was so impressed with Hamer that he recommended him to the Texas Rangers.

Like the memoir One Ranger, the first-person account by H. Joaquin Jackson (the real-life inspiration for Chuck Norris’s Walker: Texas Ranger), Boessenecker’s book includes the history of the legendary Texas Rangers from their origin in 1835 as an all-purpose state quasi-military unit designed to quell everything from Native American attacks to border skirmishes to riots in small towns policed by a single sheriff. But as Boessnecker makes clear, the famous ranger credo, “One riot, one ranger,” was often said of necessity. In fact, the Texas Rangers were always understaffed. The pay was scandalous: forty dollars a month. (One could make more as a rookie patrolman in San Antonio.) The budget was so stretched that often barracks could not be constructed, and the men were forced to pitch their own tents in the wild.

As a result, often rangers who entered nests of violence found themselves outnumbered and overwhelmed, and—as Boessenecker makes clear—they were forced to behave in ways that today we might find shocking. Hamer, who was enormous for his day (6'4" and 200 pounds), realized early that the best way to disperse an unruly gang in a saloon was to deliver a thunderous open-handed smack to the face of the mouthiest (and usually drunkest) one in the bunch. And there was an incident in 1921—when Hamer is sent to the Rio Grande see why so many Prohibition agents are being killed as they attempt to stop Mexican bootleggers.

The man explains to Hamer: “When they come across, we stand up and holler ‘Manos arriba!’ [Hands up!]. But they always start shooting.”

“All wrong,” Hamer said . . . “When I give the word, do exactly as I do.”

The moment the smugglers crossed the river, Hamer shouted “OK!” and opened fire. Six smugglers fell dead. Afterward Hamer told the agents: “Now holler ‘Manos arriba’ at these sons of bitches and see how many of them shoot you.”

The most surprising element of Texas Ranger is how often Hamer was in and out of the Rangers: sometimes leaving for better pay elsewhere, sometimes involuntarily. Ironically, it was one of his forced exiles that allowed him to pursue Bonnie and Clyde in the first place. Dismissed from the Rangers by the governor, the notorious “Ma” Ferguson, Hamer was approached by Lee Simmons, superintendent of the Texas Prison System. The Barrow Gang had engineered a bloody break from the Eastham Prison Farm, thus placing their capture within Simmons’ authority. Simmons promised Hamer all the resources and autonomy he would need if he would pursue the pair. Hamer accepted. The chase was on.

Unsurprisingly, what follows is the book’s best part, and it is downright thrilling. As Hamer picks up the scent, one can almost hear the whoosh of V-8 Ford engines as the powerful cars whip along winding gravel and dirt roads on a dragnet that stretches across six states. Boessenecker takes time to throw in a nugget or two for history’s sake, especially for those whose knowledge of the pair comes from the classic (but utterly fictionalized) Warren Beatty-Faye Dunaway film. (And yes, that film’s portrayal of Hamer is a disgrace.) We learn, for instance, that the real Bonnie was no Dunaway, was in fact originally a notorious West Dallas streetwalker who was never arrested because no one seemed to care much. “’We had bigger fish to fry than some ugly little half-pint gal with dyed red hair,’ recalled one Dallas officer. ‘So long as she didn’t roll her johns we let her alone.’”

Most poignantly, there is the famous showdown on a lonely Louisiana byway. As Hamer’s men drew their guns, Hamer found himself hoping to spare the life of Bonnie Parker. Whatever she had done, Hamer simply would rather not shoot a woman. That wish proves impossible, and both felons die with their guns in their hands.

Perhaps across the long career of this remarkable law officer, that one wish may give us the measure of the man.

Joe McDade is a professor of composition and American Literature of English at Houston Community College. He also lectures on English Composition at the University of Houston.