The First Cut is the Deepest

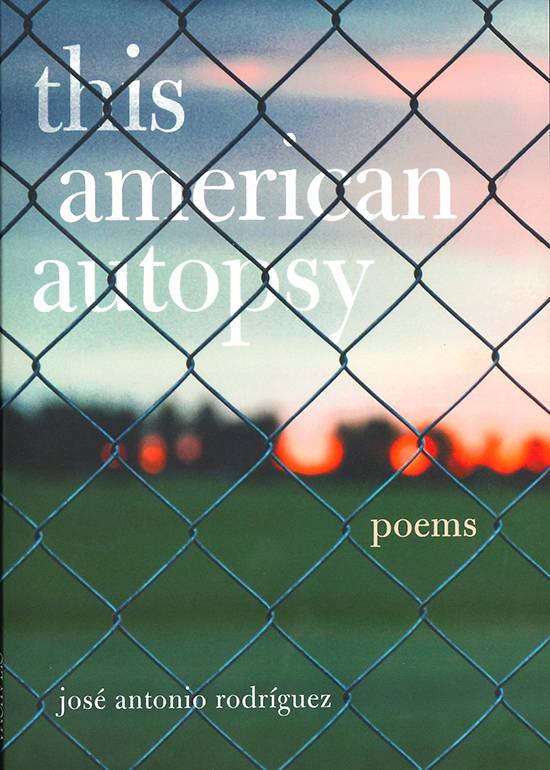

This American Autopsy: Poems

By José Antonio Rodríguez

Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2019.

76 pp. $14.95 paperback.

Reviewed by

Anthony Isaac Bradley

As promised by the book’s title, José Antonio Rodríguez’s poems explore identity, invisibility, and loss, all through a lens of violence. But make no mistake—this isn’t a collection of explicit poems, rather a focus on the aftermath that occurs outside of morgues and churches. In Rodríguez’s poem, “Kilroy,” youth equals easy prey: “First the local news: young man down / For spring break, gone missing, his body / Found days later mutilated in Matamoros, / White boys’ party town across the border.” This situation isn’t what the words “spring break” usually bring to mind, unless the context is horror movies. The line “mutilated in Matamoros” uses alliteration to sing, as if the phrase is an advertisement for a travel agency, which is the point—the tourists are newsworthy, but not the locals. “Mark was the first American victim” is a telling line, and “silk so blond” doubles down on the implication that race plays a role in the responses to these disappearances. No one cared until Mark vanished, one white man in a sea of disappearance stories.

Rodríguez continues to dwell on darker material by pulling violations from history to underscore what’s happening now. Serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer is the inspiration for “Holes in Skulls,” a poem where factory tools work on flesh instead of machinery. Dahmer’s victims were exclusively queer men, another case of invisibility that the poet highlights. Rodríguez describes Dahmer’s torture methods as “Research getting bestial,” which is effectively off-putting but not much more, as the poem never deviates from its minute details to connect to something larger. Arguably, Dahmer’s crimes are not all that different from other horrors that Rodríguez includes, but the poem itself meditates on grisly details in a way that might come off as shock value alone, clouding any other intentions the poet might have. It’s a rare misstep in the selection of included poems.

This American Autopsy is presented in two main parts: morphology and etiology, with an additional appendix for two Spanish to English translations. The poems in “Morphology” touch on childhood narratives (“Covet”) and relevant historical events (“Challenger”) while “Etiology” investigates injustices surrounding the Texas-Mexico border (“To the Sixteen-Year-Old Shot By the Border Patrol Agent”). The poems of this latter section come off as more distant compared to the previous, but this isn’t a bad thing. They never reach abstract levels, but rather feature a magnified clarity of sensory details, even if the whole picture isn’t apparent.

Not that all these poems need obvious context to understand. A speaker discovers their identity via slurs in the poem “Faggot” (author’s italics) with a lesson on manhood, at least in a patriarchal definition. “I recognized the word / When I heard it / In the school yard,” the speaker says, and without having to hear the actual slur again, it’s understood that this person realizes they are an outsider, one associated with a derogatory word they have heard before.

“Covet” features a similar voice, where two juvenile boys share an unspoken attraction: “His back to me, I guessed him wondrous / At my marks on that white sheet of paper— / The language only I knew. His lips slightly parted.” Despite the threat of violence in these poems, Rodríguez’s work illustrates a love for the human spirit.

Rodríguez’s This American Autopsy begins with a poem of tangible and non-tangible origins (“Before Stories, Or First Memory”), but ends on “Unnamed in McAllen, Texas,” a somber poem about not one person, but a community, one that exists in captivity:

And the children

And the cages

And the children

To the cages

And the man in green

And the cages

And the children play

In the cages

Rodríguez uses the repetition of “children” and “cages” to remind, but also condemn, the atrocities of ICE and border politics, as they continue to imprison and separate immigrant children from their families over Border politics. This American Autopsy is itself America’s own repetition laid bare on the table—manipulative ideals, the disrespect of bodies, and betrayal by government, repetition gutted until there’s nothing left to say.

Anthony Bradley is a graduate student in the MFA program in creative writing at Texas State University.