Lone Star Injustice

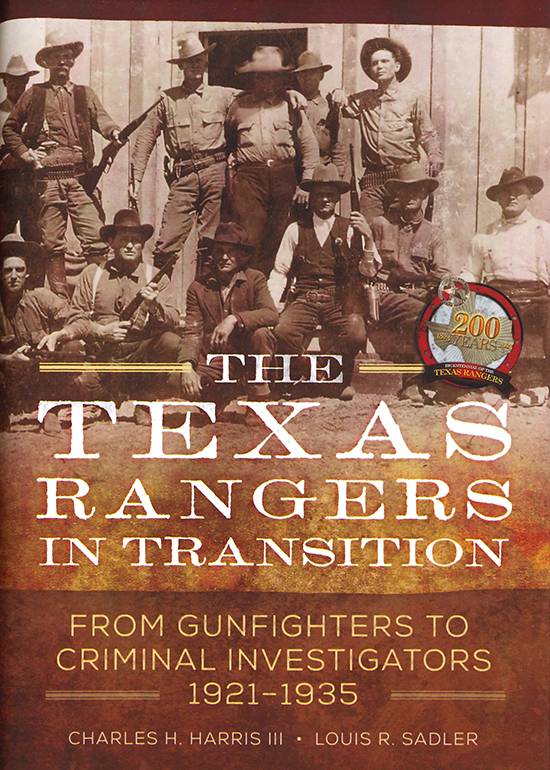

The Texas Rangers in Transition: From Gunfighters to Criminal Investigators 1921-1935

by Charles H. Harris III and Louis R. Sadler.

University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, 2019.

560 pp. $34.95.

Reviewed by

Joseph Fox

Since the release of Netflix’s The Highwaymen with its portrayal of Ranger Captain Frank Hamer and his manhunt for Bonnie and Clyde, the Texas Rangers of the 1920s and 1930s have received a renewed interest in popular culture. The story of old lawmen adapting their skills to fight modern criminals to some viewers evokes an image of the closing of the American frontier and the rise of modern Texas. It is in this light that historians Charles H. Harris III and Louis R. Sadler have written a well-researched sequel to their history of the Texas Rangers covering the 1910s (The Bloodiest Decade: the Texas Rangers and the Mexican Revolution). In The Texas Rangers in Transition: From Gunfighters to Criminal Investigators 1921-1935, Harris and Sadler continue their reappraisal of Ranger history in a decade rife with organized crime, race riots, the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, corruption from state and local political machines, oil booms, labor riots, and bank robbers now using automobiles and machine guns. The thesis of Harris and Sadler’s latest book is that the Rangers responded to these problems by transitioning from gunfighters to a modern police force working as a part of the Texas Department of Public Safety.

While in their previous book Harris and Sadler focused on the Texas-Mexico border and events fueled by the Mexican Revolution, their history of the 1920s encompasses the entire state of Texas following the activities of Ranger Captains such as William Sterling, Frank Hamer, Will Wright, Manuel “Lone Wolf” Gonzaullas, Roy Aldrich, and Tom Hickman. Part of the fun of reading a story with such a wide scope is that no matter what part of the state you live in, it will likely appear in this book because there was likely something illegal happening there and, as a result, Rangers investigating. Harris and Sadler do a masterful job of weaving new primary source documents drawn from state records with events happening at a local level. While this weaving of local history and Texas state politics communities is impressive, the drawback is that certain interesting stories are mentioned that almost merit their own book to go into more detail. For example, this reviewer would be interested to learn more about the cooperation between the Rangers and Mexican law enforcement to police the border regions, the overlap between the Rangers and Border Patrol (which began to regulate the flow of migrant labor from Mexico during the 1930s) or the political feuds in the Rio Grande Valley. Hopefully, as their previous book on the 1910s spawned bonus materials from Harris and Sadler such as The Plan de San Diego and The Great Call-Up, their overall history of the Rangers in the 1920s will spawn similar follow-ups. The reader would also be well-served by reading supplemental material on this time period such as George Diaz’s Border Contraband or Norman Brown’s Hood, Bonnet, and Little Brown Jug: Texas Politics, 1921-1928.

While constantly underfunded by the Texas Legislature, the main task of the Rangers was the enforcement of Prohibition. Despite impressive rates of mass arrests and liquor confiscation, smuggling and sale of alcohol always seemed to return because, as Harris and Sadler argued, there was always more demand for it. Also limiting the Rangers’ effectiveness was that they continued to serve at the leisure of the governor of Texas who often represented different attitudes toward both the Rangers and Prohibition. Though they benefitted from friendly governors such as Pat Neff, Dan Moody, and Ross Sterling, the Rangers constantly clashed politically with the Ferguson political machine. Aside from covering the political feuds and operations that the Rangers were involved in, Harris and Sadler spend a lot of the book debunking myths propagated by Ranger biographers or by the Rangers themselves. The Rangers in this decade began to build a mystique through radio programs, celebrities serving as Special Rangers, and histories (notably Walter Prescott Webb’s influential The Texas Rangers, which first printed in 1935) and autobiographies (like William Sterling’s Trails and Trials of a Texas Ranger). Famous Rangers of the era like Frank Hamer and William Sterling receive extra scrutiny in this book for exaggerating their accomplishments and being subject to many of the prejudices and vices common in Texas during that time. A critical eye in this regard makes for a much-needed scholarly reappraisal of the Ranger mystique. However, their ability to find virtue in Ranger history makes their work fair. Rather than gunslingers, the real hero of the book they argue is Captain Roy Aldrich who paved the way for the future of the Ranger force by organizing the group as an effective bureaucrat. While popular accounts may depict the shooting of Bonney and Clyde in 1934 as a hallmark moment in Ranger history during this era, Harris and Sadler argue convincingly that the real hallmark is the folding together of the Rangers and Highway Department into a modern police force more accountable and less prone to corruption. Whether the reader views the Rangers as heroes or villains, Harris and Sadler in The Texas Rangers in Transition write what should be considered the definitive work on the Rangers during this era and an important contribution to the history of Twentieth Century Texas.

Joseph Fox is the Associate Education Officer at the Museum of South Texas History in Edinburg, Texas, and holds a Master of Arts in history from Texas State University in San Marcos, Texas. His areas of research include Borderland and Texas Music History. He has written articles for the Handbook of Texas History, a historical marker for the Texas Historical Commission, and completed a Master’s Thesis on the relationship between Lone Star beer and the 1970s Austin music scene.