Death Is Complicated.

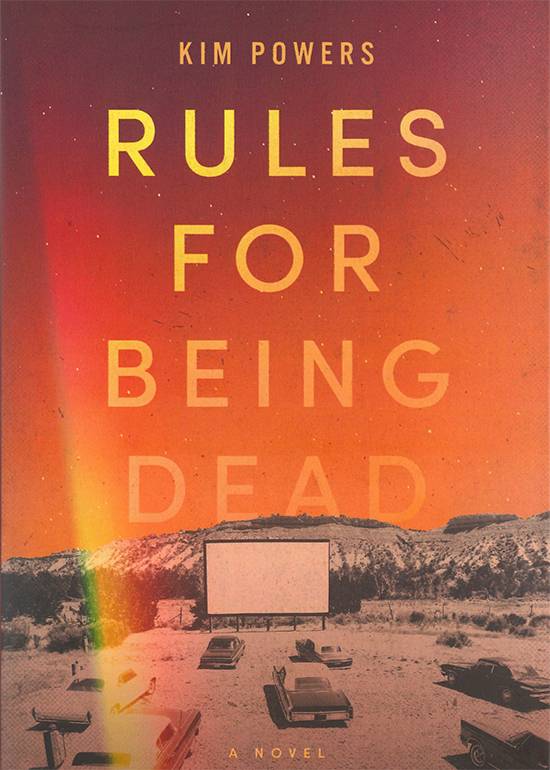

Rules for Being Dead

by Kim Powers

Durham: Blair, 2020.

297 pp. $25.95 paperback.

Reviewed by

Mary-Pat Buss

An idyllic Texas childhood consists of hot summer days, sweet iced tea in the shade, adventures set to choirs of cicadas, and sparks of fireflies flashing at night. Dead mothers are not supposed to perch in trees while their children attempt to sleep. Set in McKinney, Texas, Clarke and his not-so-departed mother, Creola, tackle this strange mystery amidst infidelity, alcoholism, and accusations of murder in Rules for Being Dead by Kim Powers. Despite the presence of vague transitions that bear resemblance to the spirit he brings to life, Powers weaves a portrait of multifaceted grief that is delicate in its complexity as it is endearing.

Few children handle the death of a parent gracefully, but Powers harnesses the tumult of loss with deft hands. Clarke challenges his father’s dominating personality by making a play for his own agency. After a physical altercation with his father, bruising forms on Clarke’s cheek prompting him to say, “I want everybody to see what he did. To me and to her.” With his mother’s undiscussed death and the corresponding lack of answers surrounding her passing, he chooses full disclosure in defiance. This break from timid, youthful acceptance is his rite of passage into early adulthood. Clarke tears at the remains of his family dynamic in his quest for answers and independence. His demonization of his father provides a focus for his grief. He can no longer remain a child when death has, quite literally, moved into his home.

Though the novel’s primary perspectives are Clarke’s and Creola’s, time is spent in the minds of supporting characters, which humanizes everyone in the novel who faces challenges associated with Creola’s death. Clarke speculates about the cause of his mother’s death and blames his father, L.E.. Seeking solace from feelings of guilt in alcohol, L.E. also strives to maintain normalcy for his fractured family. Rita, L.E.’s girlfriend, is protectively aware of the strain on the children and L.E.'s growing instability. Maurice, a seemingly uninvolved friend, wonders how he could have prevented Creola’s death. While each character tackles their inner demons, Creola’s observations act as a plot anchor that binds these personalities as the events leading to her death are unveiled. No one is entirely blameless and no one is entirely innocent. This ambiguity makes the characters genuine and whole. Much like in reality, people have complex emotions and motivations that Powers highlights with disarming skill.

Powers’s use of Creola as a mainstay is critical to the novel’s cohesiveness. While her role as ghostly mother is undeniably intriguing, it is also a source of weakness. Creola’s lack of knowledge regarding her death renders her into objectivity. While watching over her children she remarks, “I see my kids more now that I’m dead than when I was alive. Sometimes, I think I am a better mother now, dead instead of alive.” While her feelings about her children are clear, her inability to directly interact with them allows her the emotional distance needed to see the turmoil that was present in their lives before she died. Her preoccupation with her emotions once distracted her from protecting her children. As unexpected moments of clarity reveal her recent history, Creola’s flashbacks propel the plot. Powers places these moments with care. As Creola witnesses Clarke’s struggles, she similarly confronts a memory that explains a part of her final days. She sees why certain events happened and how they contributed to her family’s story. These moments of insight are crucial plot junctures that act as a hook leading to the mystery behind Creola’s death.

Unfortunately, though interesting, Creola’s rules for being dead are unclear. Sudden plot transitions and lack of clarity create a disjointed storyline. While this sensation is not pervasive through all aspects of the novel, Powers occasionally chooses to advance the plot without the painstaking care applied to character development. When it is revealed that Clarke is going to act in a movie, this huge life event is presented without ornament. Clarke transitions from dwelling on his father's lack of communication to introducing the next plot move by thinking, “I have more words than I know what to do with. Now, they’re about a movie I’m actually going to be in.” The depth of silence between father and son is contradicted by verbal performance for outsiders. The sudden introduction of this incongruity robs this theme of its symbolic beauty. In delivering this disorienting contrast without adding the needed childlike nervousness and excitement that would make the transition feel real, Powers renders this portion of the story unremarkable. The new event does not seem concrete until Clarke appears on a movie set, and even this achievement is minimalized amidst larger emotional upheavals.

Powers is adept at portraying familial turbulence. Even with a ghost mom perching atop the nearest tall object, this quirky addition to the mass of stories that tackle family conflict is a fresh, original approach. The intersection of death, grief, and the hope that growth will spring anew may not be typical of every Texan’s childhood, but through his depiction of complex characters and the myriad of motivations people face while grieving, Powers achieves a heartfelt, intriguing read that is ideal for a long Texas night.

Mary-Pat Buss is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Communication, Cultures, English, and World Languages at Texas Lutheran University. Her research focuses on minimized feminist voices and disability studies, while her work as a nonfiction writer also explores lessons in empathy and representation. She is a nonfiction winner in the Coalition of Texans with Disabilities Pen2Paper competition, and a D.H. Lawrence Society fellowship recipient.