Goodbye, Horses

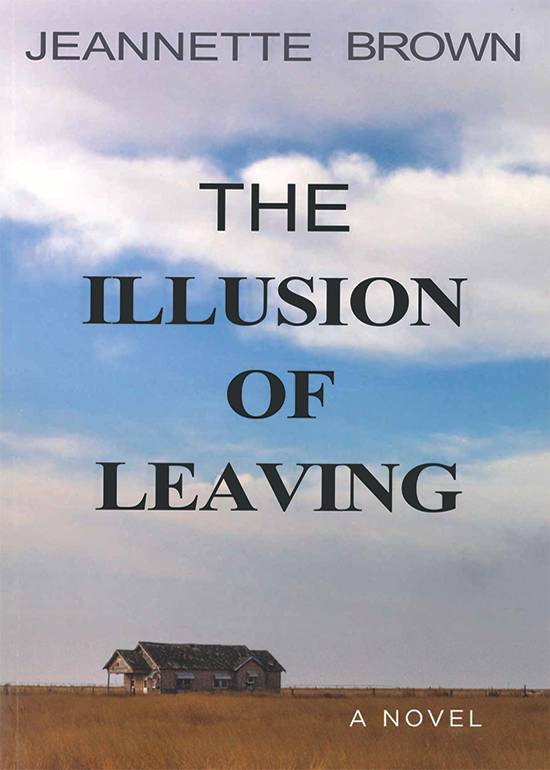

The Illusion of Leaving

by Jeannette Brown.

Huntsville: Texas Review Press, 2020.

225 pp. $21.95 paperback.

Reviewed by

Jennifer Ricks

Jamie Wright must face her upbringing in small town Silver Falls as her father slowly passes away in the local nursing home. Jeannette Brown’s most recent publication, The Illusion of Leaving, encapsulates small town West Texas, its people, and its landscapes at their best and worst. Secrets, lifelong regrets, and self-reflection are the themes of this tale. The most striking element of Brown’s convincing, engaging, often humorous work is the protagonist who is learning to get comfortable in her sixty-two-year-old skin.

Central character, Jamie Wright returns to her fictional hometown of Silver Falls to wait for the inevitability of her local-ranching-legend father, Big Jim, to pass. While she waits she contemplates her future and what will become of her father’s ranch. Jamie is in her early sixties and not happy about having to spend time in her hometown. While trying to avoid her ex-husband, she fantasizes about returning to Dallas and what she will do with her inheritance.

Over the course of Big Jim’s passing, and subsequent funeral, Jamie reconnects with two women who were her childhood best friends, Wanda and Gina, and their shared histories emerge uncovering long buried secrets. Jamie, Wanda, and Gina face challenges of aging and reconciling unresolved trauma. While Jamie learns of long ago betrayal by the two men she trusted most, Wanda comes to terms with a long kept secret, as well as a new struggle that plagues her. Gina realizes how damaging holding on to the past has been and learns to let go.

The three West Texas women reunite through a series of chance encounters, wild West Texas weather events, and common ties. Together they unravel threads of their past that they never knew were knotted and come to value one another’s insight. Being women in their sixties, they grapple with the contrast of how they once believed their lives would turnout compared to where they have landed, “remembering their hopes and dreams as young women who were about to step out into the world, and how irrelevant those dreams became.” Brown’s real accomplishment with this work is a heroine who is not young and on the verge of creating her identity, but a woman who has lived much of her life and is redefining herself regardless of age.

The title’s relevance is clear as Jamie realizes she has always carried her life in Silver Falls with her, never truly leaving it behind. For more than forty years she has held on to her father’s expectations, and to her perceptions of consequences. Jamie comes to see how these unmitigated ideas prohibited her and her daughters from having a close relationship with her father, and that she was wrong about some of her conceptions.

Contributing to the authenticity of the narration are the sweeping descriptions of the landscape, flora and fauna, the long drives, and the fierce, rapidly changing weather. The accuracy of these depictions keep the reader in the moment as events unfold, and maintain the believability of the characters’ behaviors and attitudes. Miles of horizon, red dust, tumbleweeds, cotton fields, jack rabbits, and tornadoes populate Brown’s novel as background, and as catalysts for the actions of Jamie and the community of Silver Falls.

In attempting to portray personal growth, undertones of racism and implicit biases toward the Latinx community surface throughout the novel but are not satisfactorily resolved. Personal growth for Jamie in this regard seems imminent, and it does occur but not as much as one would hope. There are subtleties that imply the people of Silver Falls are mostly white and that Latinx members of the community have historically been laborers. Jamie’s surprise at her attraction to Ernesto Rubio, a man she initially assumes is a gardener because of his ethnicity, is punctuated by her thoughts of how her father would not approve of her talking with Ernesto, and her wishing him away. Descriptions of Ernesto read overtly stereotypical including his reference to a Mexican beer as being “from the motherland.” Jamie does not allow herself to entertain the possibility of her attraction to Ernesto until she learns that he and her father had been friends. This caveat overshadows the intended message of acceptance. Instead of Jamie making decisions of her own free will, the implication is she still needs her father’s approval. It is not a completely missed opportunity by Brown, but it falls short of the type of growth one hopes to see in a protagonist when racial issues arise.

The need for Big Jim’s approval also carries over into Jamie’s decisions about her future. Although Jamie confronts her past and comes to terms with misconceptions that have haunted her entire adult life, her father’s opinions continue to whisper through her mind.

Jamie’s real triumph is seen through her processes of discovering long hidden truths about her family, her life, members of her hometown, how she lets go of shame, embraces herself, and stops running away from anything she believes may be unpleasant. Some of her discoveries bring pain, some understanding, and some joy. Jamie learns regardless of initial emotional response, facing truth ultimately brings peace.

Jennifer Ricks is an MA Literature student at Texas State University, graduating in the spring of 2021. Her undergraduate studies were in Anthropology, minoring in English. She lived in Lubbock, Texas, for six years, and worked in public education for twelve years before continuing returning to college for her Master’s.