True Texas

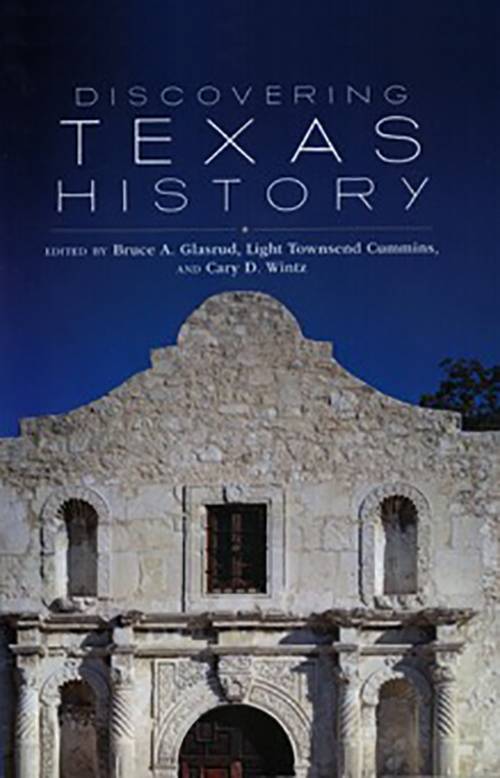

Discovering Texas History

Edited by Brude A. Glasrud, Light Townsend Cummins, and Cary C. Wintz

Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014

312 pp. $24.95 cloth.

Reviewed by

Jesús F. de la Teja

Texas historiography has come a long way since John H. Jenkins published his Texas Basic Books back in 1983. His original list of 224 “essential” titles was mostly concerned with the frontier phase of Texas history during the nineteenth century. To his credit, Jenkins included titles by the prominent Mexican historian Vito Alessio Robles and premier Mexican American historian Carlos E. Castañeda, as well as works documenting the Mexican side of the Revolution. He also included some items dealing with events before and after, but like most Texas history fans, it was the revolution and Texas’s role in American westward expansion that made up the core of his list. A few years later, one of the editors of the present volume, Light Cummins, co-edited A Guide to the History of Texas, which took a markedly different approach, attempting a more balanced, scholarly representation of Texas historical literature as well as commenting on the archival repositories available to further expand the state’s historiographical horizons.

Then came Walter Buenger and Robert Calvert’s Texas Through Time which tackled head on the thorny issue of Texan historical myopia. Talking about the extended “shelf life of Texas history,” they chastised the state’s history community for parochialism, chauvinism, and resistance to change. In 2011 Buenger and co-editor Arnoldo De León revisited Texas’s historiographical landscape in Beyond Texas Through Time: Breaking Away from Past Interpretations, in the introduction of which Buenger argues that since publication of Texas Through Time there has emerged new historiographical perspectives, although traditional approaches persist. In essence, revisionists are gaining ground on traditionalists, who have eschewed much of the racist and sexist terminology that characterized earlier generations of Texas history. Moreover, a distinctly new approach, which Buenger characterizes as “new cultural studies,” is challenging the revisionists’ own attachments to established cultural norms. What this all means, really, is that Texas history is being written by more people with more interests, and from more perspectives than ever before.

The above review does not do the subject of Texas historiography justice, but it provides a basis on which to discuss Discovering Texas History. The volume’s organizational principle is straightforward enough, there are eight topical chapters followed by seven chronological ones. The authors of almost all the essays are prominent members of the Texas history establishment, including luminaries such as Arnoldo De León, Alwyn Barr, Randolph Campbell, Carl Moneyhon, and Rebecca Sharpless. Among the topics they tackle there are the more obvious, such as Mexicans, African Americans, and women, but also less often visited areas such as

“Native Americans” and “Literature, the Visual Arts, and Music in Texas.” These latter two essays, in particular, make clear the expanding worlds of cultural and interdisciplinary studies that increasingly inform the writing of Texas history. And, all of the topical essays provide evidence of the growing interest—at least among scholars—for topics in the twentieth century and in the area of underrepresented populations, what is commonly referred to as subaltern studies among post-modernists.

This is not to say that either the individual authors or the emphasis of any of the essays could be considered postmodernist. In fact, most of the chapters might well fit in the category of bibliographical essays; their objective more to note what prominent work has appeared on which topics sans an examination of their theoretical or methodological merits. One prominent exception is Moneyhon’s review of Civil War and Reconstruction literature, which more than any other takes an analytical approach to the works he considers. In some cases there is little the author can do but simply point out important works, as for instance Todd Smith’s herculean effort to cover Spanish, Mexican, and Republic Texas in a single essay that had previously appeared as an article in the Southwestern Historical Quarterly. Also, a perusal of the title index at the back of the book confirms the volume’s emphasis on monographs over articles. This particular minor deficiency can well be overcome by using search engines such as JSTOR and Project Muse to search for periodical literature along the research lines discussed in the essays.

Discovering Texas History does a couple of important things. First, it provides an updated guide to the available Texas historical literature, particularly in monograph form, for students and young scholars. In this regard, it is a worthy follow-on to Cummins’s earlier A Guide to Texas History and admirably fulfills its primary goal. Second, it reinforces the growing sense of inclusivity that has marked Texas history studies over the last thirty years. Topic areas that were once marginal or woefully underdeveloped are shown to have flourished and become mainstream. Consequently, Discovering Texas History should find a place on the shelf of every Texas history graduate student and scholar. It will prove a useful starting point for any project.

Jesús F. de la Teja Texas State University