Let's Rock!

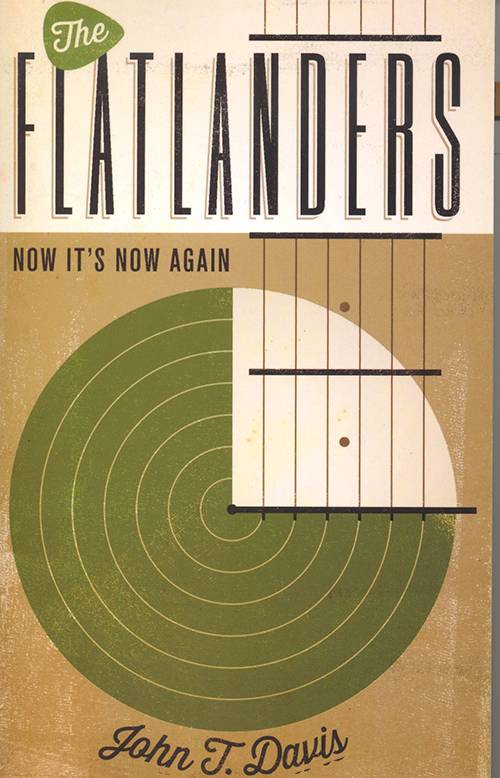

The Flatlanders: Now It's Now Again

by John T. Davis

Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014.

210 pp. $19.95 cloth.

Reviewed by

Jason Mellard

John T. Davis takes on quite the challenge in telling The Flatlanders’ story. For most of the book, they are, as one of their album titles suggests, more a legend than a band. The basic narrative is this: Three artists, Joe Ely, Jimmie Dale Gilmore, and Butch Hancock, meet in 1960s Lubbock. Together, with other musicians and friends, they catch lightning in a bottle in that moment when countercultural experiment, singer-songwriter artistry, and traditional country music cross paths in the Hub City. The Flatlanders make a demo in Odessa that opens doors in Nashville. The resulting album goes nowhere, the group gigs some around Texas, and then the artists split to follow their own paths. Those paths continue to crisscross and converge, those Nashville sessions are re-released in 1990, and The Flatlanders reconvene to new acclaim. Davis argues that their journeys, as single artists and as a group, are the bedrock of the genre we now call Americana.

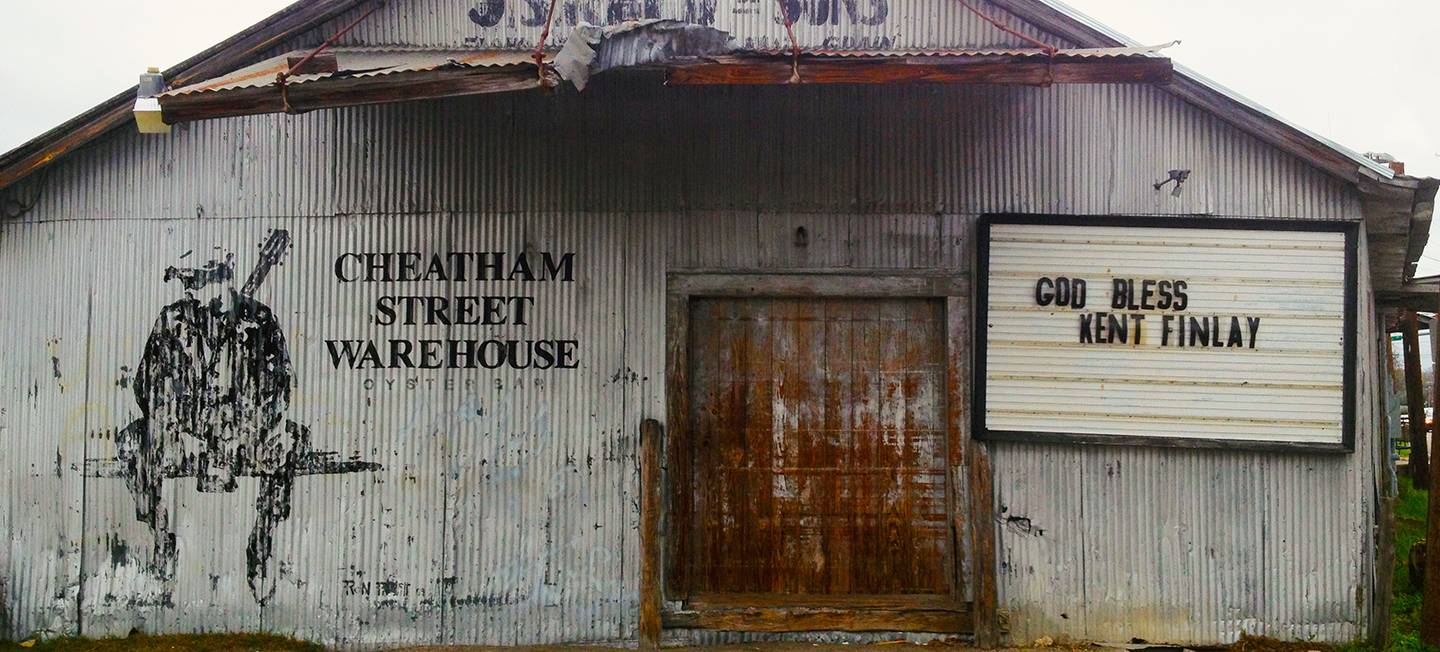

This all seems linear enough on the face of it, but Davis tells a much richer, funnier, and more poetic story amidst this collection of facts. His Flatlanders is not just an artist biography, but a collective portrait of both the city that shaped the group and a West Texas generation. The book’s Lubbock insists on a “civic identity obsessed with lines, grids, and order,” but it is also a place of rich existential fervent that nurtures artists by giving them an endless horizon to plot against. The documentary Lubbock Lights has explored some of this ground, and Davis makes use of the film’s insights as well as a range of interviews from across The Flatlanders’ careers to craft the definitive book on its subject.

The Flatlanders unfolds in five parts: “The Land,” “The Men (First Verse),” “The Music,” “The Men (Second Verse),” and “The Return.” It begins with Lubbock and the land that surrounds it, “the circle of earth and sky that shaped [The Flatlanders] in the beginning and that still informs their music and worldview.” After exploring the early West Texas rock ’n’ roll of Buddy Holly and his peers, Davis identifies The Flatlanders’ origins in a modest house near Texas Tech where, in the late sixties and early seventies, a group of young idealists gathered to talk and laugh and write and play music. The second section contains two parts. On the one hand, it looks to those “compañeros” who made The Flatlanders possible, such as Sharon Ely, Tommy X. Hancock, Lloyd Maines, Tony Pearson, Sylvester Rice, Steve Wesson, and C. B. Stubblefield. On the other, this section is also one of two moments where the book breaks to treat the separate biographies of “Joe, Jimmie, and Butch.” Those biographies will astound those new to the subject and please longtime fans.

These are, after all, three of the most original characters in Texas Music: Jimmie Dale Gilmore the Buddhist sage, Butch Hancock the architect and Big Bend guide, and Joe Ely the rocker who has torn up stages with the likes of the Clash. Juggling the Flatlanders story and these individual biographies often breaks the book’s narrative flow. It can convolute the chronology with episodes occasionally repeating several times across the text. Then again, ironing out these narrative threads so that they are just as flat as Lubbock might be what Davis is trying to avoid. He lets the experiences of “Joe, Jimmie, and Butch” fold over and double back in timelines that mirror our lives in that they are not always as neat as we might wish them to be.

The third section takes us back to The Flatlanders brief brush with success in 1972. After recording demos in Odessa, a Nashville studio picks them up, but their attempt to market The Flatlanders to mainstream country audiences through such channels as truck-driver DJ Bill Mack goes nowhere. As Davis notes, Nashville showed its tone deafness in a moment when The Flatlanders’ sound would have resonated with youth audiences discovering traditional music through Los Angeles country-rock and Austin progressive country. Nothing comes of the recordings, and the Flatlanders go their own ways.

Rounder Records’ release of those 1972 Nashville sessions as More a Legend than a Band in 1990 brought new attention to the group, and eventually led to The Flatlanders performing together again. By 2002, they had re-united for a new album. Other records followed, including those fascinating original demos, The Odessa Tapes, unearthed and released in 2012. These recordings, together with a triumphant 2013 Carnegie Hall performance, form the book’s coda and deliver on the subtitle’s cryptic promise that “now it’s now again.” “It’s kind of a full-circle thing,” as Butch Hancock puts it.

The Flatlanders is the latest in UT Press’s American Music series edited by Peter Blackstock and David Menconi that also includes volumes on Ryan Adams, Merle Haggard, and Dwight Yoakam. While some gender and race diversity in terms of subject matter would be welcome, the series is developing into an accessible and indispensable library of Americana. John T. Davis’s The Flatlanders adds much to this conversation. It stands out as the group’s definitive history and is a study of interest to those in the wider fields of Texas history, popular music, and something we just might start to call Lubbock Studies.

Jason Mellard

Assistant Director, Center for Texas Music History

Texas State University