Just Talking About My Generation

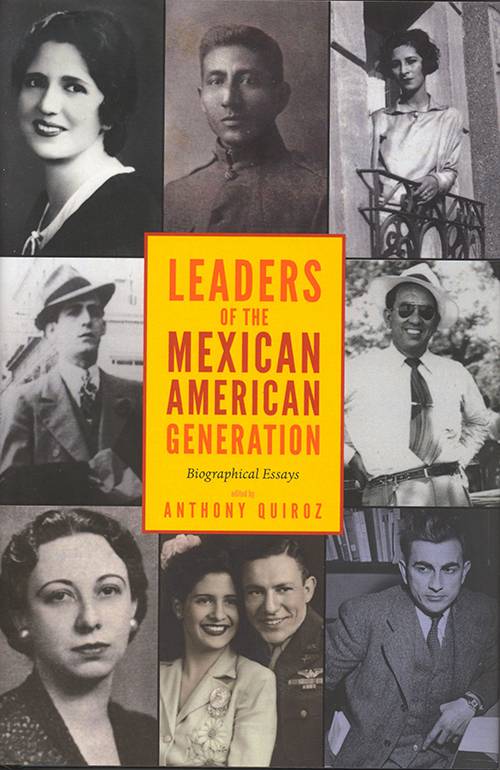

Leaders of the Mexican American Generation: Biographical Essays

edited by Anthony Quiroz.

Boulder, University Press of Colorado, 2015

368 pp. $34.95 cloth, $24.95 paper, $19.95 eBook

Reviewed by

Gene Preuss

Anthony Quiroz, a professor of history at Texas A&M University – Corpus Christi, has assembled thirteen biographies from a group of noted historians and writers in Leaders of the Mexican American Generation. The result is an impressive collection of essays that sheds light on several of the important historical figures of the period. Quiroz defines the Mexican American Generation as the period between 1920 and 1960; a time when the Mexican American community in the United States grew due to natural increase, immigration from Mexico as a result of the Mexican Revolution and economic opportunity, and an increased awareness of economic disparities and social and legal inequality.

Quiroz explains that as the Mexican population grew in the predominantly southwestern parts of the United States, both the native-born and immigrant Hispanic communities faced a “deeply rooted, pervasive racism.” Although beyond the scope of the present book, others have noted that the Anglo population in these areas was also increasing at the same time, taking advantage of dry-land farming and agricultural technology that replaced the ranches and open territory. Some have framed this as a “clash of cultures,” but Quiroz focuses on how the Mexican American generation was focused on their claim as American citizens “to gain access to the American dream as full citizens,” but he notes this “did not mean a desire to abandon one’s Mexican heritage. Rather, it reflected a desire to create a complicated bicultural identity.” In doing so, the Mexican American generation laid out the basic principles of empowerment and cultural growth that successive generations built upon, and still remain relevant today.

The various biographies in the volume cover a broad range of leaders, from those you would expect to see treated, including the well known Gus García, Alonso Perales, Héctor García, and Vicente Ximenes. Quiroz also commissioned biographies of those who receive less attention, such as Edward Roybal, José de la Luz Sáenz, and John J. Herrera. Although the anthology is overwhelmingly male-centric, as Quiroz admits, there are important treatments of women such as Luisa Moreno, Jovita Gonzáles Mireles, and Alice Dickerson Montemayor. In fact, the essays on Moreno by Vicki L. Ruiz, María Eugenia Cotera’s work on Jovita Gonzáles, and Cynthia Orozco’s chapter on Alice Montemayor are a few of the outstanding works in the collection. Quiroz, who also wrote a nuanced essay about the enigmatic San Antonio lawyer Gus García, should be commended for his effort to include scholarship by such a broad array of respected historians and writers who covered a wide variety of individuals from the Mexican American generation.

Quiroz introduces the approach he and the other writers take by explaining for the reader why they chose a generational model. This approach was established by Rodolfo Alvarez in 1973, and later expanded by Mario T. Garcia in 1987. Quiroz and his collaborators in this volume worked from the premise that “each distinct generation existed in a discrete social cultural and political environment” and because the leaders of the Mexican American generation came from diverse backgrounds and environments, it is important “to understand the complexity of this generation.” Given the diversity of the leaders in the book, historian Arnoldo De Leon askes a pertinent question in the book’s forward: Was there a Mexican American generation? This is similar to the question that historian Peter Filne posed in his 1970 essay in the journal American Quarterly, “An Obituary for the ‘Progressive Movement.’” In the article, Filne reasons that historians have had such difficulty defining “progressivism,” aligning the various factions, characters, ambitions, goals, and methods of the various reformers who did not always agree on what was “progressive”, that there indeed may not have been the common intentionality to justify calling the period of reform a “movement.” Given the disagreements, the differing backgrounds, and the competing organizations that were founded during this period, it is easy to understand why some might question whether the Mexican American generation really existed.

Quiroz introduces the approach he and the other writers take by explaining for the reader why they chose a generational model. This approach was established by Rodolfo Alvarez in 1973, and later expanded by Mario T. Garcia in 1987. Quiroz and his collaborators in this volume worked from the premise that “each distinct generation existed in a discrete social cultural and political environment” and because the leaders of the Mexican American generation came from diverse backgrounds and environments, it is important “to understand the complexity of this generation.” Given the diversity of the leaders in the book, historian Arnoldo De Leon askes a pertinent question in the book’s forward: Was there a Mexican American generation? This is similar to the question that historian Peter Filne posed in his 1970 essay in the journal American Quarterly, “An Obituary for the ‘Progressive Movement.’” In the article, Filne reasons that historians have had such difficulty defining “progressivism,” aligning the various factions, characters, ambitions, goals, and methods of the various reformers who did not always agree on what was “progressive”, that there indeed may not have been the common intentionality to justify calling the period of reform a “movement.” Given the disagreements, the differing backgrounds, and the competing organizations that were founded during this period, it is easy to understand why some might question whether the Mexican American generation really existed.

Yet, this collection of biographies reveals that rather than operating singularly and in competition, organizations like the League of United Latin American Citizens, American G.I. Forum, Alianza Hispano-Americana, or what became the National Council of La Raza, most of the members of the Mexican American Generation operated with and within multiple organizations, what Quiroz describes as a “web of connections.” He points out that “These professionals embraced a set of commonly accepted ideals that defined American citizenship” and passed these along to subsequent generations. Despite the fact that subsequent generations developed additional organization and goals, and often looked down on what they considered the assimilationist methods of the Mexican American generation. Quiroz and his colleagues demonstrate that the ideal set forth by the Mexican American generation—to equally celebrate their culture and heritage without giving up their rights as Americans—have not dimmed. This book will be of interest to students of the American West and Southwest, Borderlands studies, American studies, politics, and Mexican American studies.

Gene B. Preuss is Associate Professor of History at the University of Houston-Downtown and specializes in the history of minority education in Texas. His book, To Get a Better School System: One Hundred Years of Education Reform in Texas, was published by Texas A&M Press in 2009, and A Kineño’s Journey: On Family, Learning, and Public Service, with former Secretary of Education Lauro F. Cavazos, Jr., will be published by Texas Tech University Press in 2016. For fifteen years, he served as an editor for H-ORALHIST, the H-NET discussion lists dedicated to oral history. He is a member of the Houston Independent School District’s Hispanic Advisory Committee, is active in the Texas State Historical Association, is a past-president of H-NET Council and the East Texas Historical Association, and advises a college student chapter of the League of Latin American Citizens.