Let's Get It On

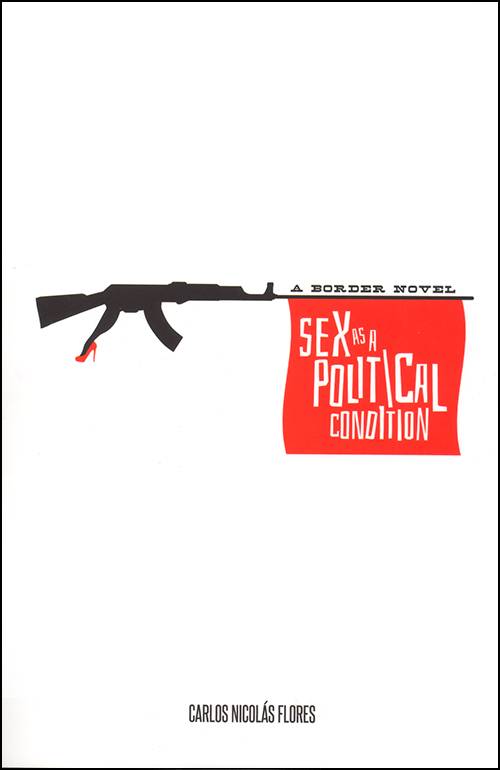

Sex as a Political Condition: A Border Novel

by Carlos Nicolas Flores

Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 2015.

406 pgs. $34.95 paper

Reviewed by

Joseph McDade

Is there humor—dare we say farce—to be found at the U.S.-Mexico border? In the enchantingly titled Sex as a Political Condition: A Border Novel, Carlos Nicholas Flores makes a strong case for the affirmative.

Amid the allegations of Fast and Furious, amid drugs heading north and automatic weapons heading south, amid thoughts of a big wall—in the muddle of all this, the reader is drawn to one Honore de Castillo, a man who feasts on such as the biography of “Cuba’s most important hero, Jose Marti,” but whose own biography has placed him in the border town of Escandon, Texas, in a pathetic little curio shop, and at the mercy of loudmouthed tourists who see him as no better than the kid who cuts the grass back home. Unmanned by his hectoring wife Maruca (shades of “’Murica”?), he longs for something more, and in the grand tradition of Don Quixote, Tom Sawyer, and Madame Bovary, Honore will end up in one precarious situation after another.

The first clue to the novel’s farcical bent can be found in the names in chapter one, and seem inspired by Voltaire. Honore’s neighbor is named Joshua T. Cuervo and nicknamed, of course, Tequila. Honore’s daughter is Bonita. The friend who lures Honore into the romantic life of a revolutionary is named Juan Sanchez Trusky but known as Trotsky—the same name, of course, as the Communist Revolutionary who was murdered in Mexico by one of Stalin’s henchman. The names prepare us for what is to follow: a gaze into insanity and desperation that reads like a Latin Catch-22.

Why is this book so funny? Because it is so desperate. One can find almost daily evidence of the perilous existence that confront people on either side of the Rio Grande: the human trafficking, the routine executions of public officials, the squalor. What Carlos does through Honore is tap into a more universal desperation, one found in characters as dissimilar as Siddhartha and the Frederick Exley portrayed in A Fan’s Notes. On some basic level Honore wants to right the wrongs of the world, yes. But his deeper need, his almost animalistic craving, is to somehow matter, to belong to something larger than himself. In perhaps the novel’s most touching passage (not less because it veers off at its end), he communicates his deepest fears to Maruca:

“My greatest fear is dying in front of a television.”

She glanced sideways at him. “What’s wrong with that?”

“Trotsky says most men die like that. Stupid, inconsequential deaths. Me—I want to die on some beach in Central America, before a firing squad.”

“¡Estas loco!”

“Do you know what it feels like to wake up in the morning and discover you’re in bed with a Republican?”

“Do you know what it feels like to wake up in the morning and discover you are in bed with a communist?”

At Trotsky’s prodding, Honore throws himself into endeavors that becomes increasingly (shall we say) quixotic even as they remain (shall we say) honorable. He smuggles refugees. He runs guns to Mexican revolutionaries. He becomes involved in a bizarre tete-a-tete with radical Latina lesbians. His description keep churning and churning: “Some strange-looking women stormed inside,” Flores writes. “With close-cropped hair, they would have looked best in Nazi uniforms, swaggering around in construction boots, slouching hangdog style. He couldn’t tell if they were from Escandón or from out-of-town. Maybe Austin.”

Finally, a convoy of humanitarian aid arrives in Escandon bound for a hotspot familiar to any sentient American over the age of forty: Nicaragua. (Why, thirty years ago, Nicaragua was one of the three or four most polarizing locations on Earth can be traced, like Trotsky’s name, back to the Soviet Union.) During the journey, the adventures become more dangerous, the tone more somber, and Honore must come face-to-face with the notion of his idealism, like that of so-many revolutionaries before him, smashing against the granite-hard reality of the world. The simplicity of this exchange between Trotsky and Honore belies the sense of despair and ennui that awaits so many revolutionaries:

“Sometimes things make sense and sometimes they don’t. Sometimes your closest allies turn out to be your worst enemies. Do you know what all of this is called?”

“No.”

“History.”

Flores’s novel is sometimes overstuffed with detail, often ridiculous, but ultimately well worth the time—not just as comedy but as caution. One is reminded of a famous pop ballad by The Who, warning their own fans not to become too enamored of the next great crusade. A reader who comes to the table with Honore’s ambitions might heed Robert Townshend’s lyrics, and his vow: “Won’t get fooled again.”

Joseph McDade is a professor of composition and American Literature of English at Houston Community College. He also lectures on English Composition at the University of Houston.