Welcome to the Purple World

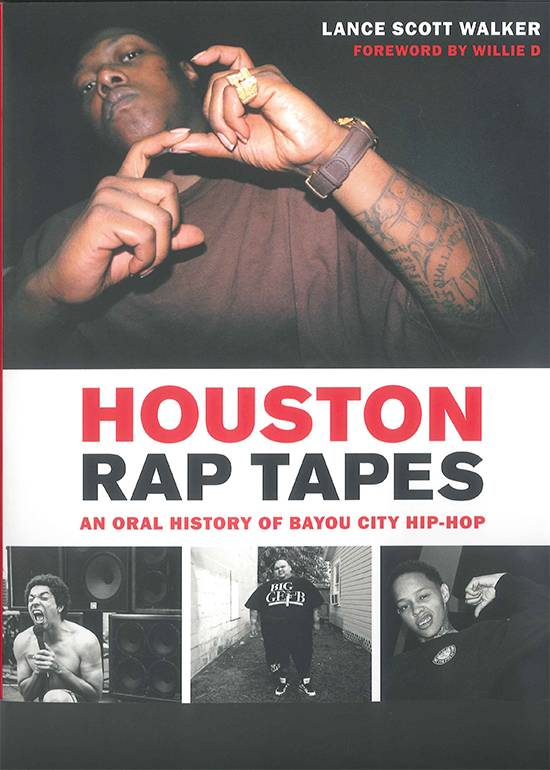

Houston Rap Tapes: An Oral History of Bayou City Hip-Hop

by Lance Scott Walker

Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018.

355 pp. $29.95 paper.

Reviewed by

Alan Schaefer

Chronicling four decades of underground sounds, the slow crawl to mainstream adulation, and the even slower tempos of a Screwtape, Lance Scott Walker’s Houston Rap Tapes: An Oral History of Bayou City Hip-Hop offers an authoritative history of one of America’s most innovative and radical music scenes. An expanded and reorganized version of 2014’s Houston Rap Tapes, the book contains twenty-two additional interviews and a host of photographs by Peter Beste and other Houston photographers. Beste’s photography remains central to the project of documenting Houston rap, and it was Beste who urged Walker to begin interviewing the artists and architects of the scene. Walker groups interviews with an eye for both history and geography. Interviews with early figures of the scene are followed by those with artists who dominated the rap battles at DJ Steve Fournier’s Rhinestone Wrangler, a nightclub in a nondescript shopping center near the Astrodome. A bulk of the book consists of interviews with Houston’s Southside rappers while the Northside rappers close the collection.

Walker’s interviews are spacious affairs that leave the doors wide open for rappers, DJs, emcees, and promoters to tell their tales of Houston’s rap scene. His introductions to each interview are insightful, orienting readers with lesser known artists, locales, and labels, but Walker lets the artists do the talking. Maneuvering the travails of the music industry and the challenges of life in the Houston neighborhoods of South Park, Third Ward, and Fifth Ward are the central topics, but Houston Rap Tapes focus mainly on the music: crafting beats, writing rhymes, and distributing product. Interviews with early innovators such as Darryl Scott, who first developed the slowed-down production style that DJ Screw would carry through the 1990s, and the various members of the Ghetto/Geto Boyz, such as Ready Red, Willie D, and Scarface, illuminate the foundations of the various styles that characterize Houston rap today. Following the mainstream success of the Geto Boyz, Houston rap and hip-hop seemed to duck back into the underground for the remainder of the 1990s, but the weight of what was brewing there would revolutionize hip-hop. Eventually, DJ Screw and his chopped and screwed production emerged, and a new music was born that might be only comparable to the sonic depths and distortions of Jamaican dub of the late-1970s. An anchor of the Houston scene and an innovator whose influence has made its way into numerous arenas of American popular music, DJ Screw’s impact is enormous. He didn’t take his work lightly, and he expected the same from his colleagues when they arrived at his home studio. Z-Ro affirms the Screwed Up Click work ethic : “[Y]ou know not to go in Screw house with no bullshit. ’Cuz for one, when you walk in there, you gonna be trapped in that bitch for three days anyway.”

The 2000s ushered a new era for Houston. DJ Screw’s death in 2000 “set off a shockwave that that sent the city reeling and the whole world around Screw scrambling,” according to Walker. Northside rappers came to the forefront while crosstown collaboration (which had at times been a risky affair due to deep-seeded neighborhood beefs) helped accelerate Houston rap’s rise to a previously unimaginable status. Rappers Bun B and Pimp C of UGK, Paul Wall, Mike Jones, and Slim Thug brought their rhymes to mainstream, and DJ Michael Watts of the Swishahouse label carried on Screw-inspired production practices. Walker’s interviews with the acclaimed Northside rappers offer some valuable conclusions on the history and various trajectories of Houston rap, and the book’s final batch of interviews with young, contemporary artists concludes a project that is boundless in its exploration and definitive in its documentation.

In addition to rappers, producers, DJs, and label honchos, Walker interviews significant members of the scene such as Meshah Hawkins, who came up in the early ’90s with the Screwed Up Click and was the longtime partner of Big Hawk, older brother of rapper Fat Pat. Hawk was murdered less than a month after marrying Hawkins. She succinctly notes the integral role that DJ Screw’s music plays in the car culture of Houston: “You ain’t ridin slab if you ain’t bangin Screw.”

Houston rap has been closely surveyed by industry moguls, critics, and fans while nevertheless remaining an underground treasure of the Bayou City, distributed from popped car trunks and independently owned record stores. Lance Scott Walker, who is currently at work on a DJ Screw biography, knows well the need for documentation of these valued Texan musical forms, and he offers a dream realized for fans of Houston’s explosive rap scene.

Alan Schaefer is a Senior Lecturer at Texas State University. He is an editor for the Journal of Texas Music History, and he is the author of Homegrown: Austin Music Posters 1967 to 1982.