Urban Power

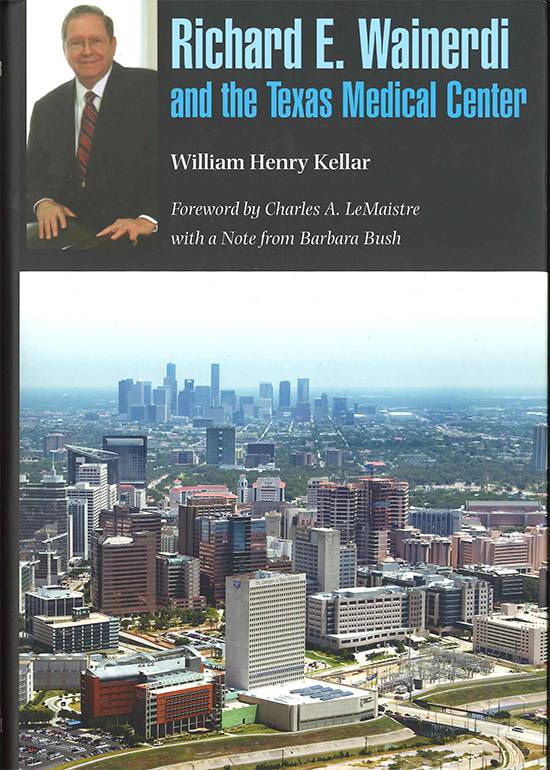

Richard E. Wainerdi and the Texas Medical Center

by William Henry Kellar

College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2017.

256 pp. $25.00 cloth.

Reviewed by

John Mckiernan-González

Unlike some of our sports facilities in our cities here in Texas, the fiscal and physical infrastructure of hospitals and research facilities is nearly invisible, with the exceptions of ambulances, traffic slowdowns and occasional city-wide bonds. The seemingly taken-for-granted just beyond the visible nature of much of our contemporary medical institutions can be tragic, given that hospitals and clinics are the place where people and professionals connect private insurance, Medicaid, Medicare and household savings to medical outcomes. William Kellar does a wonderful job at making the management of these complex and crucial urban institutions personally gripping and intellectually satisfying. Richard Wainerdi and the Texas Medical Center starts with a broad framing question: “how was it that a kid who was born in Depression-era New York City, and raised in the Bronx in a single-parent household, ended up as the longest serving president of what became the largest medical complex in the world?” Kellar provides readers with three broad answers to this question. First, politically prominent individuals, communities and corporations in the Southwestern United States recognized and fostered the prodigious intellectual and organizational talents Richard Wainerdi had to offer. Second, Wainerdi’s journey through Texas A&M, Gulf Oil and the Texas Medical Center offers a glimpse into the way key elected officials in Texas and Oklahoma leveraged federal funds and institutions to build an environment that embraced medical investment as a key part of urban development. Third, Kellar points to the importance of professional networks in the United States during the Cold War. William Henry Kellar’s institutional biography of Wainerdi traces myriad sets of networks connecting public schools in New York and the South, geology and cold war nuclear science, to the emergence of international professional networks linking higher education, oil extraction, and medical institutions in Texas to the world. Richard Wainerdi’s double migration from working-class Bronx neighborhoods to elite circles in Texas and from Texas A&M University to the Texas Medical Center in Houston are part of the story of class mobility and public spending that pushed the rise of the Sunbelt in American culture.

Piecing together this book must have been an intellectual challenge. Richard Wainerdi was one of the youngest people to gain a professorship and a deanship at Texas A&M, he helped bring techniques generated in vastly expensive nuclear laboratories to bear on geology and chemistry. This work then gained him one of the top prizes in chemistry – the Hevesy Medal. After becoming skilled in campus interdisciplinary politics and outreach to elected officials while maintaining an active research agenda, Wainerdi stunned most people at A&M when he resigned his professorship. He then went on to become CEO for Prizenuclear Geology, presidency of Gulf Oil in the aftermath of the oil embargo of 1973. In 1984, Wainerdi became the president and CEO of Texas Medical Center, bringing his engineering, political and oil networks to bear on the growth and management of more than 93 medical institutions. Both Kellar and Wainerdi find ways to communicate the challenges facing Wainerdi in these different institutions, bringing out both the social and intellectual dimensions of nuclear research and corporate management.

Kellar and Wainerdi’s collaboration provide some unexpected insights into institutional development. Wainerdi highlights the importance of barbecues in DC as key networking sites during LBJ’s time as Senate Minority leader and president; he uses the reorganization of dining halls in Gulf Oil corporate headquarters to bring out the importance of food to institutional cohesion and, finally, Wainerdi points to the importance of parking construction to enhancing the everyday life and thus fomenting a shared institutional culture across the different research centers, clinics and hospitals that make up the TMC. There is even a high noon moment when Wainerdi and the TMC faced down and defeated Rick Scott and HCA [Hospital Corporation of America, then Humana] over their attempt to turn a charity hospital into a for-profit link in their HMO; the line TMC drew in the sand against the health-care profiteers contributes to the successful litigation of the largest medical fraud case in U.S. history, Columbia HCA v. Texas.

Kellar and Wainerdi’s decision to refuse to address the political orientation of elected officials removes a filter that many people use to view the past. This decision allows readers to see a wider commitment across Texas to building TAMU, NASA and the TMC; it also allows Wainerdi and Keller to discuss the different pathways to upward mobility in higher education, transnational corporations and non-profit institutions. That same dimension renders the earth-shaking place of the Civil Rights movement in Texas politics relatively invisible; the only discussion of civil rights is that Wainerdi refused to put up a wall to separate the Texas Medical Center from the surrounding city. This decision to focus the story of the TMC around Wainerdi’s tenure leaves out some of the small democratic d dimensions of the TMC:

The educational institutions enrolled 34,000 full-time students and provided research facilities for 7,000 visiting scientists, researchers, and international students. Approximately 160,000 people visit the Medical Center every day, a place where the hospitals deliver 28,000 babies and surgeons perform 350,000 operations annually. The Texas Medical Center has an economic impact of some fourteen billion dollars on the Houston area, and today there is no other medical complex like it anywhere in the world.

Much of the pleasure in reading this book is the coziness and comfort between Wainerdi and Kellar. Ultimately, this book documents Wainerdi and Houston’s broad and successful defense of medicine as a public good in Texas. This is a key book to understand how Texas and the Southwest rose to prominence during the Cold War; a book that offers important insight into the role of the knowledge economy in the fuller transformation of Jim Crow Houston into the diverse, segregated and industrial research hub it has become.

John Mckiernan-González is the Director of the Center for the Study of the Southwest, the Jerome and Catherine Supple Professor of Southwestern Studies, and an Associate Professor of History at Texas State University. His first book, Fevered Measures: Public Health and Race at the Texas-Mexico Border, 1848-1942 (Duke, 2012), treats the multi-ethnic making of the U.S. medical border in the Mexico-Texas borderlands.”.