He Knows The Score

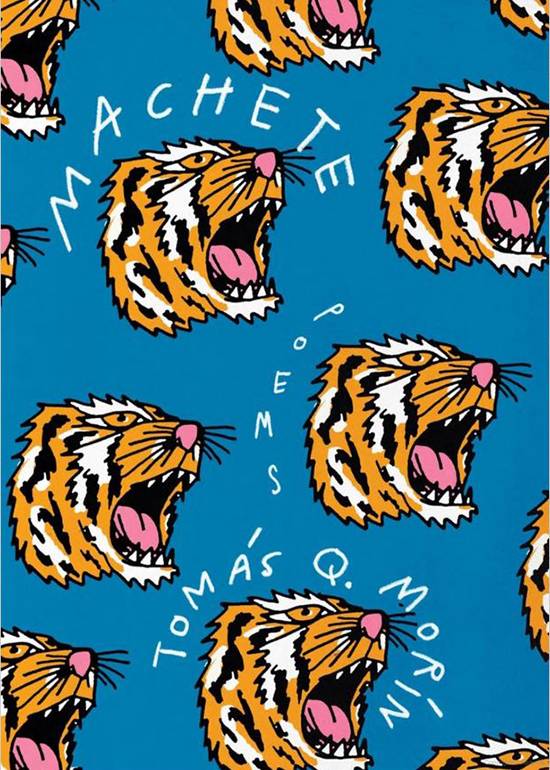

Machete

by Tomás Q. Morín

New York: Knopf, 2021.

96 pp. $27.00 hardcover.

Reviewed by

Riley Welch

Amid a global pandemic, Tomás Q. Morín set to work on his third poetry collection, searching for connection in a time of isolation. Morín’s latest brings together the turbulent nature of the past few years—politically and pandemically—and the chaotic character of new fatherhood through pop culture references and detailed, mundane images cast in new light.

Morín’s opening poem, “I Sing the Body Aquatic,” connects his sweaty palms to the body of a fish, swimming through the sweat like water. He says when he shakes hands,

“I know

When our hands embrace he’ll find

proof of natural selection

in the shape of my fingers, evolutionary

holdovers from an era of gills.”

In the back of the book, Morín provides reader notes for certain pieces, of this one, he says, “Had my sometimes sweaty hand and feet never been diagnosed as acute hyperhidrosis, I would never have thought to trace my origins back to the sea.” This becomes a theme through the collection: painting of an ordinary scene in an extraordinary way. Something as simple as a sweaty handshake becomes the ocean, making readers think more about their routine day-to-day actions, how they could unfold into another world.

In his poem, “New Year’s Eve,” Morín explores the Racial Dot Map of America. Listing the colors assigned to different races:

“Green dots are blacks, blues are whites,

orange are Latinos, red are Asians, and brown

are Native Americans and everyone else.”

He goes on to question the map’s existence at all, the further division in an already divided country, “If this is what passes for hope/then what are the green dots/between my tulips and the sea?/Maybe somewhere green dots still mean grass./In America blue dots are an ocean/full of fish with no gills. I need to believe I can breathe/underwater.” Beautifully recasting the rigid number game of the Racial Dot Map into something more human and tangible.

The titular poem, “Machete” also explores the othering of race in America, opening with the lines, “When they stare/I know it is my skin.” He continues to draw metaphor between those who stare and sugar cane, comparing his smile to a machete that can cut the cane down: “I sharpen the edge of my smile/and watch them fall.” He is showing his reaction to blatant racism, his choosing to smile in the face of discrimination. Though this initially seems like a passive act, the machete acts as a weapon to fight against the discrimination. He ends the poem back with the sugar, how he loves it in his cake or coffee,

“where they give up

the sweetness

they make me take

one slice at a time.”

This details the devious nature of racism, the way something can act as a microaggression or ignorance, making him take it, disguised as sweetness. By turning his smile to a machete, his can take power back from the situation, “one slice at a time.”

Morín’s work is highly accessible, lacking in overly flowery language without taking away from the poetics of his work. He also does this in subject matter, using pop culture focal points in a way that may be unfamiliar in tone to a more traditional sonnet or romantic piece. In his poem, “Sartana and Machete in Outer Space,” dedicated to Jessica Alba and Danny Trejo of Robert Rodriguez’s Machete series, Morín speaks from the perspective of Sartana, a main character in the film and writes a new, poetic narrative. Creating an imagined monologue, there is a tongue-in-cheek feel to some of the lines: “He did find me here in space./You could say our love is galactic now.” But Morín is able to pull in beauty, even if the reader is unfamiliar with the Machete franchise: “all babies born today/were born under a bad sign./The blister on my heart/and this machete in my hand say different.” His poems “Miles Davis Stole My Soul” and “Machetes” in the latter half of his book do this as well. Pulling together personal experience and collective pop culture creating a new way for readers to view existing pieces of art.

Many of the poems in the second half of the collection focus in on Morín’s life, shifting to a more personal and autobiographical voice. Many of his poems deal with new fatherhood amidst a global pandemic. In his poem “Two Dolphins,” he begins at the building of a crib and takes us on a winding journey through the sleep deprived eyes of a new father. The poem is melancholic at times and funny at others, trying to find the proper name for a man’s breast as he rocks his son back to sleep, invoking the title towards the end:

“My breasts are two dolphins

with electronic gear

strapped to their heads

who stare with goody grins

when they’re asked

to do something

simple like swim.”

Like his opening poem, Morín gives a new perspective to the mundane. A man’s breast are not usually the centering topic of a newborn, but Morín shows us the wanderings of his mind in the night, the places they may go when sleep is no longer easily accessible.

Like the title might suggest, Morín’s collection is cutting. It asks us to experience life through the lens of metaphor, seeing the world in ways we likely have no considered previously. Whether tackling big issues like racism in America or the isolation of a global pandemic, or more ordinary pieces of life, like hyperhidrosis, Morín examines each scene through new perspectives, his words carefully written and inviting the reader to savor each word.

Riley Welch is a poet from Texas. Her work has appeared in Authentic Texas Magazine and Hobart After Dark, among others. She is a current MFA candidate at Texas State University, where she serves as Assistant Managing Editor for the Porter House Review. She makes a great loaf of banana bread.