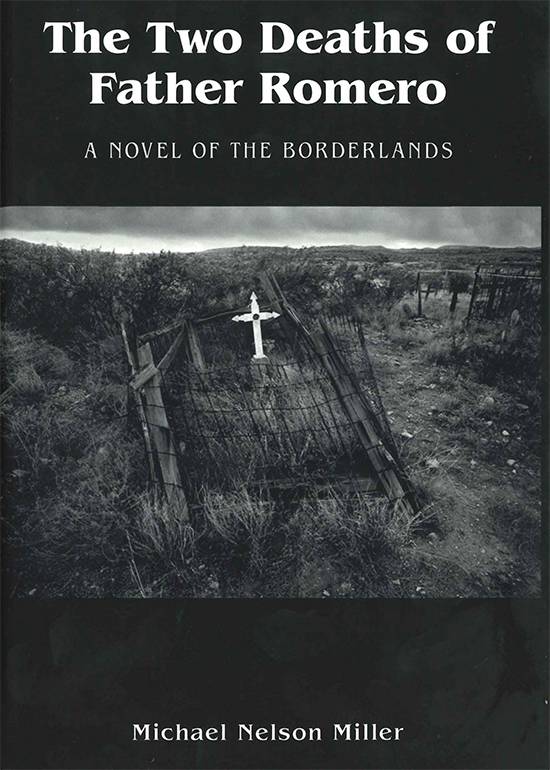

Borderlands

The Two Deaths of Father Romero

by Michael Nelson Miller

San Francisco: Blurb Press, 2021.

213 pp. $25.00 hardcover.

Reviewed

by Idza Luhumyo

In Michael Nelson Miller’s The Two Deaths of Father Romero, the reader is presented with a mystery embedded within the fabric of the Texas borderlands. Much of the story is set in Dolores, a small town near Mexico. Crafted as a loose whodunnit, the novel introduces the reader to a motley cast of characters who, coming from different parts of the United States and Mexico, find themselves embroiled in the drama of the murder of Celestino del Toro (‘Tony’).

Prior to his death, Tony was a college student dispatched to Dolores by his wealthy Mexican family in a bid to toughen him up and keep him from keep causing drunken trouble in Northern Mexico. But to enrol in the Range Science program at Sullivan State, Tony had one condition: his friend Alberto, the son of a mistress to a wealthy political figure in Chihuahua City, had to come along. His parents agreed and the two found themselves causing havoc and engaging in “bitter, drunken, mirth” in this “backward Texas border town into which they could never, ever fit.” However, soon after the two enrol—and in unclear circumstances—Tony is murdered. This prompts his father to enlist the expertise of a detective to find the killer, thereby setting the stage for the novel’s plot.

Part of the allure of The Two Deaths of Father Romero is that the story moves quickly, aided by short chapters, snappy prose, and swift characterization. These stylistic choices give the novel the momentum and tension to keep a reader invested. Here is an example of a paragraph from the novel’s early chapters:

Hobard sits at a crossroads. A main highway runs west to Waco and East to Corsicana. A farm to market road runs north into the Czech area, and a town called Penelope, where the school is Catholic. The phones are answered with a cheerful ‘Ahoy, Jak se ma?’ The road south disappears into the fields and doesn’t seem to go anywhere.

The Two Deaths of Father Romero is first and foremost a novel of place. While we only ever get brief character sketches of the various people interested in finding Tony’s killers, the author spends enough time delving into the history and culture of Dolores. Indeed, what the novel might lack in poetic fancy, it makes up for in a story well-researched and grounded in a place, so that to finish the novel is also to understand the town’s history. You could be dropped in the middle of the town and find your way around. There is also the sense that an air of despondency hangs ever about Dolores and, indeed, the novel. From the moment the detective hired by Tony’s father sets foot in town, the reader understands that something is coming home to roost—that whatever ensues in the novel is sure to disrupt the town’s deceptively placid façade. Additionally, bubbling under the novel’s superstructure is a consideration of how places shape people and, in turn, how those people go on to shape those places. In doing this, the novel becomes a celebration—if not idealization—of the ethos of small towns: the slowness; the nosy neighbourliness; the sense that everyone is in everyone’s business; and the guarding of open secrets.

The novel also complicates conventional notions of home and belonging. Even though most of the people who call Dolores home are transients, they take a lot of pride in being considered locals of a tight-knit community. Perhaps tellingly, while the identity of Tony’s murderer is revealed at the end of the novel, The Two Deaths of Father Romero is not so much about the identity of Tony’s murderer, as about capturing the complex history of the borderlands, a place that—according to the narrator—is inhabited by “people who live on the margins—the indigenous, drug dealers, prostitutes, pickpockets, the homeless, taxi drivers, beggars, street Marias with feverish, snotty babies…broken, forgotten pieces of human pottery.”

That said, the novel’s strongest feature may also be its weakest. In prioritizing a sense of place and presenting the characters one after the other in short and brisk chapters, the novel develops the kind of narrative tension that keeps a reader flipping the pages as the story gallops towards a resolution. At the same time, this presentation of character sketches in quick succession—without making it immediately clear how they are related to each other—gives the novel the veneer of a puzzle whose coming together some readers may be too impatient to wait for. Still, as a novel with a strong sense of place, The Two Deaths of Father Romero succeeds in narrating one of those stories that stay with you with long after the final page is turned.

Idza Luhumyo is a graduate student at Texas State University.