Cómo Soñar

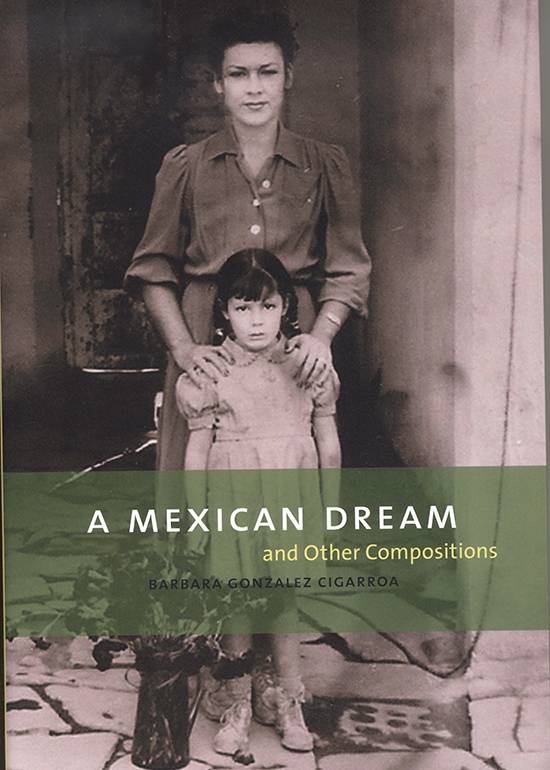

A Mexican Dream and Other Compositions

By Barbara González Cigarroa

Fort Worth: TCU Press, 2016.

160pp. $29.95 cloth.

Reviewed by

Edward Santos Garza

One insulting thing about politics in the United States is how some politicians, namely those who are children or grandchildren of immigrants, regard their family's pre-American life. In their recollections, such life was a mere prelude to success, a prelude to leave behind, philosophically if not also physically, as soon as God allowed. You and I know the template: "When my [insert family member] immigrated from [insert country] during the [insert era of strife], [he or she] brought with them [insert values Americans believe they exceptionally possess], a respect for [insert 'hard work' or ‘freedom’] and [insert sum of money less than $1,000]. Because of them, I stand before you today as [insert a simplistic, 'common' American identity]."

Ironclad as the narrative seems—nothing wrong with hard work—its tellers usually side-step issues of assimilation, prejudice, and privilege. ('Grit alone does not a successful politician make.') Moreover, their family's life in the old country is described as bereft of its own dignity, of beauty. The old country serves only as a gauntlet through which the brave ancestor discovers how much they desire freedom, how no country besides America could suffice as their home. The brave ancestor is Dorothy Gale, and Ellis Island (or the Florida coast, or the U.S.-Mexico border) marks the moment her world takes on color.

Of course, to paint history this way is to ignore the spectrum of American experiences, the myriad ways in which one can be an estadounidense. Immigration is beautiful, but our national rhetoric too often lacks the language to chart it. The result, carried out by politicians (or ourselves) is a truncated consciousness, a particular sense of rootlessness (and that's for those of us who have the privilege of studying our genealogies in the first place). Thankfully, books such as Barbara González Cigarroa’s A Mexican Dream and Other Compositions subvert the gospel of a one-size-fits-all American self.

A daughter of the Texas frontera and an esteemed immigration judge, Cigarroa writes poignantly about what it means to be from the border, crafting her text in vignettes (essays, letters, profiles) devoted to members of her family tree. Refreshingly, she starts her historia in México, weaving tales of her grandmother and great-grandmother. Reading about Cigarroa’s compassionate, witty abuelita, for instance, one observes how strength is passed from mother to daughter, from daughter to granddaughter. One understands how history upheaves the lives of even the most prosperous, compassionate people, how a family must adapt with each generation while remembering its past.

Perhaps because Cigarroa is good at rendering lives concisely, my favorite passages are those that give A Mexican Dream its broader shape. I think particularly of passages about the borderlands, expositions that capture the beautiful, unique qualities of both lados. The following is from maybe my favorite page of the book:

From my home in Laredo, the other side meant Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, and Mane’s [Cigarroa’s grandmother’s] delicious arroz con pollo, tamarind popsicles sold by corner vendors, bustling marketplaces, and plazas with fountains. It meant an area where I could walk anywhere on sidewalks lined with trees whose trunks were painted white; and where my primas, my cousins, spoke a perfect Spanish different than my Tex-Mex, looking so confident in their high heels. It meant a place of beauty and warmth where family life encompassed everything, and children were free to play in the streets from morning through dusk.

Though I’d enjoy more panoramic shots such as this, they appear frequently enough to keep the text from feeling confined.

Vivid as A Mexican Dream is, there are indeed moments in which I desire more vividness, more human messiness. For a while, I couldn't put my finger on what's missing in some of Cigarroa’s key passages. What I've concluded is that this book's familia is too dream-like. There are shenanigans, sure, but no one here really has a personality flaw, a vice. Of course, airing family chisme is just one reason most humans don't write memoirs, but personal essays can't be just about virtues. This reservation in the text, combined with Cigarroa’s formal voice, sometimes impedes the intimacy A Mexican Dream strives to share.

But in some cases, how a story is told is less important than the fact that it's told at all. At its core, Cigarroa's book is about Latinx success amid adversity, about how pride in one's roots bestows strength. As such, A Mexican Dream should enlighten other people about the fortitude, the wisdom of America's largest minority. Thus enlightened, other people might consider more scrupulously what histories, what artworks—what policies—actually show a respect for Hispanic lives.

Even more importantly, Latinxs reading this book might see themselves beyond the plebeian image that mainstream media project at them. They, like Cigarroa, might understand that their spiritual homeland isn't traced by a river, mountain, or highway, but rather by the hands of their ancestros. American poets in their own right, Latinx readers should come away from this book celebrating the multitudes they themselves contain, singing their own songs in their own lenguas. Qué así sea.

Edward Santos Garza has published work in the Houston Chronicle, Enculturation: A Journal of Rhetoric, Writing, and Culture, and Praxis: A Writing Center Journal. He’s a graduate of the University of Houston and Texas State University, where he earned his Master of Arts in Rhetoric and Composition.