The Long Valley

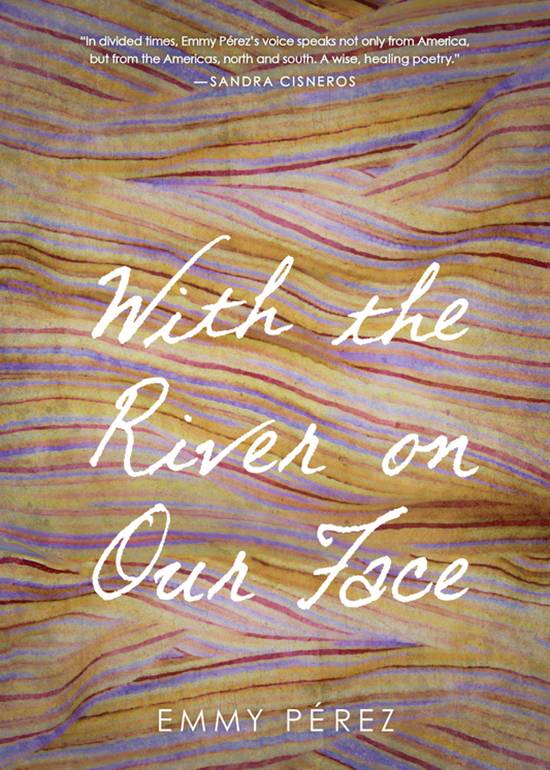

With the River on Our Face

By Emmy Pérez

Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2016.

104 pp. $13.92 paper.

Reviewed by

Octavio Quintanilla

Disclaimer: Due to our website’s formatting, we cannot display Pérez's poems in their original form.

I n her most recent poetry collection, With the River on Our Face, Emmy Pérez takes us on a hike up and down the Río Grande (aka Río Bravo), showing us its banks at El Paso and then south to El Valle (aka the Rio Grande Valley). Although these poems are a celebration of the region’s people, flora, and fauna, Pérez also calls attention to social issues that persist in this part of America, specifically with those having to do with the militarization of the South Texas border.

Pérez opens the collection with the poem, “And it’s you,” establishing tone and subject matter as well as pointing to the poetics that compose the five sections that follow. The poem begins with a scattering of lines on the fertile soil of the page: “It is you / I know it’s you / It’s you / And you / And you.”

The poem continues its incantatory flow down and across the page, interrogating what it means to be part of a landscape that is beautiful yet marred by violence. On her stroll down the banks of the Río Grande, the speaker places us at the center of the earth, and by doing so, she makes us witnesses the cruelty that occurs here, violence like a living thing, just like the carrizo, the dragonflies, and the river rats: “What I forgot to say is that violence passed there / blood spilled there / blood spilled here / red dragonfly red dragonfly / little hawks little hawks.”

The speaker’s mind jumps from watching the small harmless elements in nature to the unspeakable violence that the land remembers. The poem ends with the speaker wanting the violence “expired, expelled, expired-expelled.” The violence is not expired nor expelled. It continues its path “Downriver,” the title of Part I, where Pérez insists for us to open our eyes and see the Rio Grande Valley as a place that exists, alive:

el Río Grande exists

inside el Río Bravo

resacas and canales

San Benito water tower

with Freddy Fender’s portrait

This place is no mere metaphor, no mere battlefield for greedy politicians. It is alive with montes, wild creatures, and people. A cartographer of language, Pérez maps the fluidity and vibrancy of the Rio Grande Valley by cataloguing what has always been here, and which outsiders, sometimes natives, often fail to see: a living, thriving place, a place teeming with life and culture. Anyone who has driven on Expressway 83 from McAllen to Brownsville, or vice versa, has undoubtedly seen the water tower on the side of the road with Freddy Fender’s smiling face. Pérez includes these details to counter oversimplification and abstraction: she wants our senses to awaken, to see carrizo and chapulines; to hear chachalacas and the rattle of snakes; to taste toronjas and sugarcane; to get lost in the ébanos and montes. It is all here, these images, these nouns, scattered like seeds on the page.

In section II, titled, “Midriver,” Pérez evokes the river, the “río,” not as a metaphor, but as a homophone of “real”: real existence, real erasure of existence. In the poem, “Left after crossing,” for instance, the speaker imagines “River wet / panties / rolled off / the body” left behind “in the shade of an ébano,” or “in a monte,” or “in a sorghum field.” The speaker hopes that the woman:

discarded

[her] panties for a dry

pair from a sealed

plastic bag

to enter

Tejas

comfortable

Although the poem ends on a positive note, what is truly called forth is the brutality experienced by those who make the crossing, a brutality often experienced at the hands of those who are supposed to guide them to the gates of the American dream.

In the poem, “The History of Silence,” Pérez defines erasure: “to erase, erasus / From to scratch / To scrape,” and then taking on the voice of the aggressor, the poem orders us not to “comment on memory / The screaming / Didn’t happen.” But something did happen. The speaker asks: “My sister’s bones. / Where are they?” No one answers. But we know the answer. If you have lived on the border, you must be familiar with the answer. Here, by juxtaposing what is articulated and what is left unsaid, Pérez engages our sense of place, and consequently, the history of violence associated with that place: Ciudad Juárez-El Paso; Reynosa-Hidalgo; Ysleta-Zaragoza; Matamoros-Brownsville, and the list goes on.

“Río Grande-Bravo” is the title poem of section III of the collection, a long meditation on the poetic line. Here, Pérez weds poetics with politics. Here, the Río Grande~Bravo is divided in half: it “has an invisible line down its center / An invisible caesura / on water…” By using poetic concepts to describe the Río Grande, Pérez wishes for nothing more than to heal, as poetry tends to heal, what has been torn, what has been divided: “Where I want to apply stitches / Like skin healing.” But liquid can’t be stitched like skin. The implications are subtle: writing poetry is a political act. It is resistance, especially when the speaker tries to “remember [her] love / Of the poetic line, of poetic breaks / And the patrol / Van hasn’t moved in an hour.” How to write poetry when you are being watched by men in uniform? Men who could be your nephews, your godsons? How to write poetry when every line of your body is at the mercy of someone else? When all you see are walls and those who see you are those who watch the walls? How do you break a border wall with words? With poetry? Although the speaker of the poem transmits a sense of helplessness: “Can’t write anything / To halt the wall’s construction,” the poem ends with the speaker’s desire for love: “And when I wake up in the morning feeling love / And when I wake up in the morning with love / And when I wake up in the morning and feel love / And when I wake up in the morning already loving / How the body works to help us feel it.” This is what we must sing to ourselves, the poem suggests, a poem in which the “line is the beloved,” a poem in which the line is always, always the beloved.

In the final two sections of the collection, IV and V, “Cara” and “Boca,” respectively, Pérez gives us a sense of what it means to live and love on the border amidst agents, detention centers, and a border wall. “What is it to love,” the speaker asks, “within viewing distance of night / vision goggles and guns.” The poem raises questions: How is this way of living normalized? Despite all the intrusions, violations, and suspicions from those who guard the border, people continue to live and love: “I used to love you / with the river on my face / I still love you / when the river’s on my face.”

This poem reminds us of the importance of the river to the borderlands, how it is the center of the people who live and love on both banks. Its importance to those who have never crossed it, and to those who dream of crossing it someday. In section V, the poem, “Not one more refugee death,” reminds us that “we are all connected / by water, la sangre de vida.” And this, perhaps more than anything else, is true for those who live along the river.

As an appendix, Pérez includes a useful section of “Notes and Works Cited.” If we missed it in the poems, here we find the sources of lifted lines, allusions, and definitions that she intertextualizes. Figures such as Sappho, William Carlos Williams, Li-Young Lee, and Gloria Anzaldúa make appearances. Anzaldúa, for instance, is a significant presence in this collection, providing the collection’s epigraphs and serving as muse, curandera, and poetic chalan.

Overall, Emmy Pérez, like other border writers before her, and writers who will surely come after her, gives voice to the powerful river that in many ways defines the region along the Texas/Mexico border. It is an honest voice, a voice worth reading and worthy of attention. The question is: who, other than we, who live and love here, by this river, is listening?

Octavio Quintanilla is the author of the poetry collection, If I Go Missing (Slough Press, 2014).His work has appeared in Salamander, RHINO, Alaska Quarterly Review, Southwestern American Literature, The Texas Observer, and elsewhere. He is a CantoMundo Fellow and holds a Ph.D. from the University of North Texas. He is the regional editor for Texas Books in Review and teaches Literature and Creative Writing in the M.A./M.F.A. program at Our Lady of the Lake University in San Antonio, Texas.