Whistling Dixie

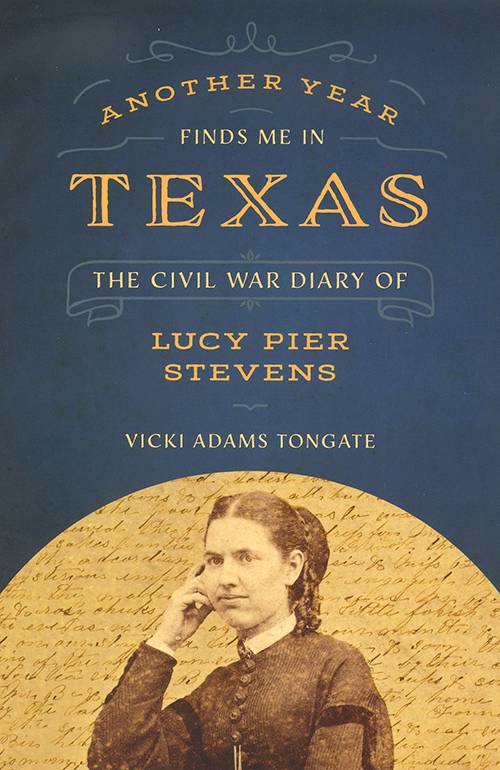

Another Year Finds Me in Texas: The Civil War Diary of Lucy Pier Stevens

edited by Vicki Adams Tongate

Austin: University of Texas Press, 2016.

367 pp. $29.95 cloth.

Reviewed by

Rebecca Sharpless

For decades, people interested in the Civil War experience in Texas have found rich material in the published diaries and letters of women such as Elizabeth Neblett, Harriet Perry, and Maria von Blücher. These primary sources yield excellent insights into the terror of the Civil War, even one far away geographically, and the myriad details of daily life. Now the observations of another woman have been added to those—with a twist: Lucy Pier Stevens was a Yankee, an Ohioan stranded in Austin County, Texas, when the war broke out. Stevens's diary adds nuance to our understanding of a nation divided, as she details her accommodation (frequent) and resistance (rarely, and seldom direct) to the Confederate side of things.

In this volume, carefully edited by Vicki Adams Tongate, Stevens describes life in Austin County almost daily, from January 1863 through her return to Ohio in May 1865. Tongate introduces and concludes each chapter with thoughtful analysis, and her lengthy annotations of the text add clarity and context. (An earlier volume of Stevens's diary, covering 1861-62, also exists but came to the editor's attention only after many years' work on the annotation of the 1863-65 volume.)

Twenty-one-year-old Lucy Pier Stevens came to Austin County to visit family in 1859. Her aunt and uncle, Lu Merry Pier and James Bradford Pier, had settled in Austin's colony in 1835. They built a prosperous life with their three children and by 1863 owned four slaves. Lu Merry Pier and her older daughter, Sarah Pier (later Wiley), also kept journals, now housed at the Texas Collection at Baylor University. Tongate appropriately alludes to these journals to round out Stevens's entries.

Lucy Pier Stevens is an appealing character, apparently even-tempered and uncomplaining. Stuck in Texas by the war, for more than two years she cannot exchange letters with her immediate family north of the Confederate border. Only occasionally does her very real homesickness for Ohio break through. Her diary entries vary in length between one line and several pages, and she has a keen eye for detail.

On New Year's Day 1863, the diary opens with a description of a nice day: dinner that included "sure enough coffee," some sewing, and company. At the end of the entry, Stevens notes, "Uncle Pier heard a report that Magruder had taken Galveston.” And so it goes throughout the diary: everyday activities, friends, family—and always concern about the war. Stevens shows no particularly political bent, and her worries are often local. She frets about the well-being of Confederate soldiers whom she knows from Austin County—well-founded, as several of them die in southern service. The residents of the area are mostly fearful about the Louisiana campaign and the possibility of a Union invasion of Texas, but they also receive news (albeit frequently inaccurate) about the larger war to the east.

Besides a short supply of coffee, life in Texas is otherwise fairly comfortable. The new year's party, for example, features three kinds of meat, sweet potatoes, fried eggs, egg bread, and tea and cake. The women spin, weave, and sew almost constantly. Although paper is precious, it never runs out, and the family writes a steady stream of letters. The slaves make few motions toward freedom, despite whites' fears of insurrection. As did many white well-to-do southerners, Stevens and her peers entertain themselves by visiting and reading some of the most popular fiction of the day, such as Macaria by Augusta Evans and the novels of Sir Walter Scott.

A reader unfamiliar with the nineteenth century will be struck by the omnipresence of death in the diary. Stevens recounts three epidemics in as many years: measles, typhoid, and yellow fever. Babies died frequently, and Stevens records her grief at the death of her tiny namesake, Sallie Lu Bell. Austin County soldiers, like Civil War participants everywhere, died more frequently from disease than in battle.

Through it all, Stevens maintains her equilibrium until, in January 1865, a letter finally gets through from Ohio, detailing the deaths of thirteen friends and family members, including Stevens's beloved younger sister, Juli. From that time, she begins to plan her return north. Three months later, she boards a blockade runner in Galveston, heads for Havana, and arrives home sometime in May. The edited diary ends there. The afterword tells us that Stevens married Joseph Caldwell in 1867 and had two daughters.

The diary eventually found its way to the DeGolyer Library at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. Vicki Tongate has done a masterful job of editing, with numerous helpful tools such as a cast of characters and a three-part timeline setting episodes in Stevens's world alongside other Civil War events. Through her good agency as well as those of the DeGolyer Library and the University of Texas Press, Lucy Stevens's diary is available for all readers who would learn more about an Ohio woman who spent the Civil War in Texas.

Rebecca Sharpless is professor of history at Texas Christian University in Fort Worth. She is author, most recently, of "'In Favor of Our Fathers' Country and Government': Unionist Women in North Texas," in Texas Women in the Civil War, edited by Deborah M. Liles and Angela Boswell.