Jailhouse Rock

Convict Cowboys: The Untold History of the Texas Prison Rodeo

by Mitchel P. Roth

Denton: University of North Texas Press, 2016.

379 pp. $32.95 paper.

Reviewed by

Jessica Roseberry

Mitchel P. Roth, a professor of criminal justice and criminology at Sam Houston State in Huntsville, Texas, has taken up the history of the Texas Prison Rodeo (TPR), also located in Huntsville. There is such a natural fit of the subject, location, and the author, one wonders why no one has written in depth about the TPR before. Roth makes use of material about the prison and the rodeo from multiple archival sources, and his careful examination of these sources is one of the great strengths of the book. He places the archival stories within the larger, detailed context of prison, popular culture, and Texas life. The TPR as a subject is inherently wild, interesting, human, and tragic; and Roth’s narrative is at its best when he is telling the true tales of prisoners who rode wild animals, jumped out of airplanes, risked their lives for money tied to the horns of bulls (an event appropriately called Hard Money), and who also suffered long days and long nights in a lonely, arcane prison. The writing becomes a bit clunky when Roth describes the more mundane—but necessarily informative—aspects of the TPR’s history. Perhaps if Roth had played the role of cultural critic more often, the overall flow of the book might be a bit more successful. But at the close of the pages, the reader is ultimately left with a textured, well-researched view of the TPR and its impact, and so the difficulty of integrating the archival details into narrative or into a larger cultural critique can be overlooked.

The Texas Prison Rodeo existed from 1931 to 1986, and Roth essentially chronicles each year of the rodeo’s existence, pulling out salient details and cultural moments at each point. For example, in the 1950s the prison board was besieged with letters from churchgoers asking that the rodeo not be held on Sundays. In 1959, before his famous recordings in San Quentin and Folsom Prisons, Johnny Cash came to sing “Folsom Prison Blues” at Texas Prison Rodeo in Huntsville in the rain, and the overwhelming response he got from his captive audience convinced him to go further into an outlaw image and into recording his songs before prison crowds. Even before famous acts such as Cash came to perform at the rodeo, “free-world” crowds from all over East Texas connected with the spectacle and the daring risks taken by the prisoners who had successfully auditioned to participate in the event. At its height, the TPR drew in 30,000 spectators.

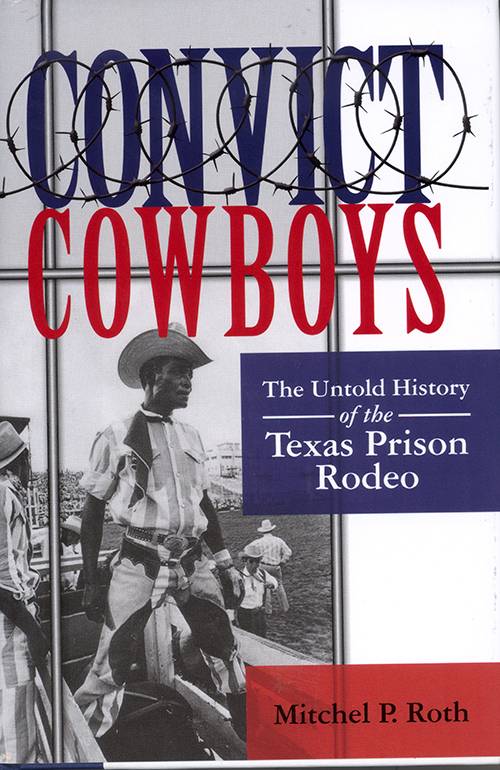

We also see, over time, the awful conditions within the prison in Huntsville. Prisoners were laborers in cotton fields, and were physically punished for infractions. Prisoners would hurt themselves in order not to have to suffer work detail (the stories about the self-mutilations are haunting). The rodeo served as an endeavor for them, a humanizing struggle that broke the routine, gave them the opportunity to win a little money and fame, and dignified their effort. When the rodeo closed in the 1980s, the prison board and perhaps the townspeople were ready to see it go, but the prisoners wanted it to stay open. Once again, it is the connection with the humanity of the prisoners and the TPR that give this book its best bite. Lots of vivid pictures most often culled from the Texas Prison Museum also offer the reader visual detail about the heart-stopping, intimate, hardscrabble nature of this yearly event.

Overall, the book provides a necessary and interesting account of a little-studied piece of Texas history. The story is about a subject that might easily be lost to time, and about protagonists who offer their physical selves in the ring as a significant part of how they are interacting with the outside world. The fact that the rodeo existed at all and that prisoners were physical entertainers changes the entire arc of their personal contributions to the historical record and to how we remember them. This alone compels exploration of the topic. Roth’s in-depth examination of the Texas Prison Rodeo as an event that served as a fundraiser for the prison and as an exhibition for free-world visitors provides the reader with new understanding of both. As Western-themed entertainment that drew celebrity acts, as fodder for the prison’s improvement fund (the use and sometimes misuse of this fund is discussed in the book), and as spectacle for crowds who wanted a cheap Sunday look at toughness and thrill, the TPR and its long life make for fine and substantial history.

Jessica Roseberry is a graduate of Wheaton College (BA, literature) and of Baylor University (MA, American studies). For almost a decade, Jessica served as the oral history program coordinator at the Duke Medical Center Archives. Subsequently, she completed an intensive oral history project, Shiloh Voices, documenting the history of a longstanding nonprofit organization headquartered in New York City. Currently, Jessica works for the Baylor University Institute for Oral History as university researcher, conducting oral history interviews in order to preserve the history of Baylor University.