Crosses on the Highway

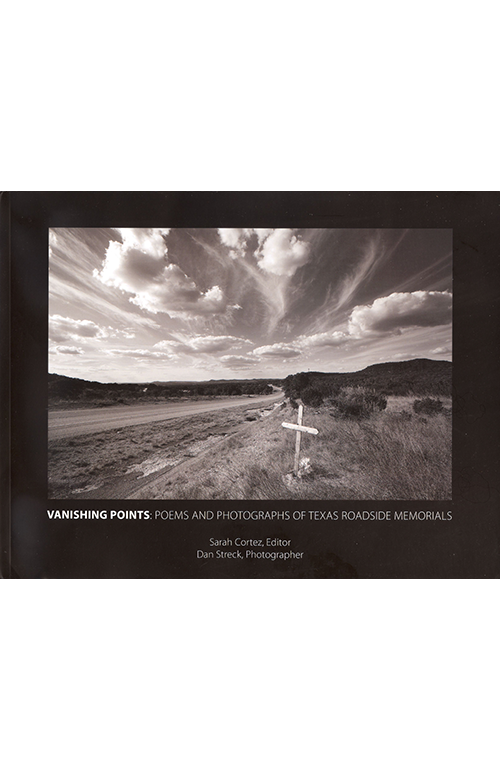

Vanishing Points: Poems and Photographs of Texas Roadside Memorials

edited by Sarah Cortez

photography by Dan Streck

Huntsville: Texas Review Press, 2016.

160 pp. $22.95 paper.

Reviewed by

Zach Groesbeck

Anyone living in Texas, rural or urban, has seen them—roadside memorials. Attached to a tree or tied around a utility pole, there’s an arrangement of flowers, a white cross, and sometimes large ribbons. Driving past these, though I’m not religious, I always make the sign of the cross, out of reverence and condolence.

Vanishing Points, a new collaborative anthology featuring photography and poetry, edited by Sarah Cortez, is a similar gesture, commemorating the many lives lost on Texas roadways. Contributors include Cortez and three other poets—Loueva Smith, Jack B. Bedell, Larry D. Thomas—as well as photography by Dan Streck. Artistically, Vanishing Points exhibits poetry’s immediate ability to collaborate with and expand upon other art forms. On its back cover, the book describes itself as “respond[ing] to the visual summons of roadside memorials with lyric intensity and eloquent ekphrasis.”

Ekphrasis, which originated from the Greek ἐκφράζειν (ekphrázein), meaning “description,” is a literary work based on a work of visual art—painting, sculpture, photo, film, etc. Although ekphrasis seems like an obscure term, many celebrated works in the canon are in fact ekphrastic. Such renderings include Keats’s “Ode to a Grecian Urn” and William Carlos Williams’s Pulitzer-winning collection Pictures from Brueghel. Although ekphrasis expounds the original artwork, it should accomplish something new, saying something beyond what has previously been said by the work described. In other words, ekphrasis is not reiteration.

The poems in Vanishing Points either verbalize a new empathy that is otherwise ineffable, transcending the inherent limitations of photography, or they don’t at all, and they simply retread the imagery of Streck’s photographs. However, these reiterations are seldom, usually subtle, and are often a smaller moment in an otherwise compelling poem.

Streck’s photographs, which comprise half of the book, are of a point-and-shoot nature. However, this is a necessary simplicity. By keeping the shots relatively plain, Streck removes the composition’s subjectivity, replacing it with the subject’s objectivity. The photos are an assortment of both longshots, which contextualize the memorials within the larger sprawl of rural Texas's interminable skies and rolling wooded landscape, and close-ups, which engage intimately with particularities. Both framings approach, without preoccupation, the gritty poignancy of the deaths that occurred there. Resisting sentimentality, Streck’s photos are blunt—blunt in the way that a Larry Clark film is blunt. They don’t say, “Here, someone’s life was lost.” Instead, they say, “Here, a person died, and a family suffered, and when you pass by these memorials, your fear makes you look away; now, now you can’t—so look, look.”

This candidness caters well to poetry by providing, not only visceral imagery, but also space in which further meaning, through an inwardly-narrowing poetic focus, can be accessed. The photo accompanying Loueva Smith’s “Wooden Wing” is a close-up of a wooden cross, depicting only one of its wings, which contrasts sharply against a bright background of blurred stems. There, in fading, barely legible ink, is written three words, “Love you Tio.”

“Wooden Wing” begins by returning Streck’s presence into the photo, asking the audience to first consider the relationship between witness and memorialization:

The photographer leans in closer with his lens

and takes a picture of a whisper.

I think it is what he has been looking for.

After comparing the faded ink to a wilting flower, Smith concludes in apostrophe, noting an ambiguity in the inscription:

Oh Tio, sweet T. Which one are you?

The one killed here, or the one who signs

this thin pine board as if it is a love letter?

Smith’s inquiry, like a majority of the poems in this book, seeks empathy—which is fundamentally the work of poetry. Smith creates empathy through the ambiguity of evocation. First, of course, the reader sympathizes with this family’s loss. Second, through the indistinctness of who has been lost, Smith expands the reader’s sense of loss throughout the entire family, and because the reader has no basis to comprehend who this family is, so the reader naturally is drawn to consider their own family. Through this uncertainty, Smith evokes a disillusionment that nears grief and bereavement.

Sarah Cortez, in her poem “Sweep,” processes the palpability of death while driving by projecting personal emotions onto the memorials, leading to contemplations of her own mortality. The poem begins:

The road’s currency is speed

and control its illusion. Risk it,

depending on tire and brake,

pistons and plugs. Don’t ponder

the probability of die-cut machinery

mishaps or hungover auto mechanics

with undiagnosed malevolent tendencies.

Here Cortez establishes, nearing an absolute, the inherent danger of roadways. The language is omniscient, and although falling into an odd subjective assumption by the stanza’s end, the third-person perspective pronounces these dangers as infallible. The tone set by this is overtly ominous moving forward. “Sweep” is a neo-formalist sonnet. Though lacking traditional elements such as a Petrarchan rhyme scheme and a lilting iambic pentameter, Cortez’s variation is still composed of fourteen lines and contains a volta—the dramatic turn in tone and content. The volta reads:

Presume you’re not only safe

but lucky. Accelerate past

the small white crosses

under sensational Texas sky.

It’ll never be you or yours

memorialized next to

the tree line’s black lace.

Cortez’s tone may get her into trouble, as it explicitly lacks empathy, making the poem vulnerable to egregious misreadings which may misconstrue her tone as merely self-serving. I say ‘egregious misreading’ because, clearly, Cortez’s poem, as a sonnet (the form inherent to love poetry), is not seeking to indict or blame, but as a loving kindness, it seeks honesty. Cortez’s tone mimics the underlying fear encountered when we all drive past the memorials. It’s part of the reason why I make the cross as I drive by. It’s part of the reason people look away. We all see these memorials, aware of the death that has occurred, and know that, not only could it have been us, but every time we get in a vehicle, it very well can be us.

Aesthetically, Vanishing Points resembles a coffee-table book. Yes, it’s dimensions are a little bit large and it contains black and white landscape photographs, but the similarities end there. The nature of a coffee table book, aside from really serving as living room décor, is to be viewed by a bored houseguest, providing casual, uninvolved spectatorship of pretty photos and light reading of depthless captions, a transitory experience. Vanishing Points, by relentlessly confronting death, is a work that wants to be talked about afterwards. Unlike its namesake, which describes perspective lines receding into a horizon, Vanishing Points is a beginning, crossing the horizon, into a new threshold.

Zach Groesbeck studies poetry in the MFA program at Texas State University.