Friday Night Hero

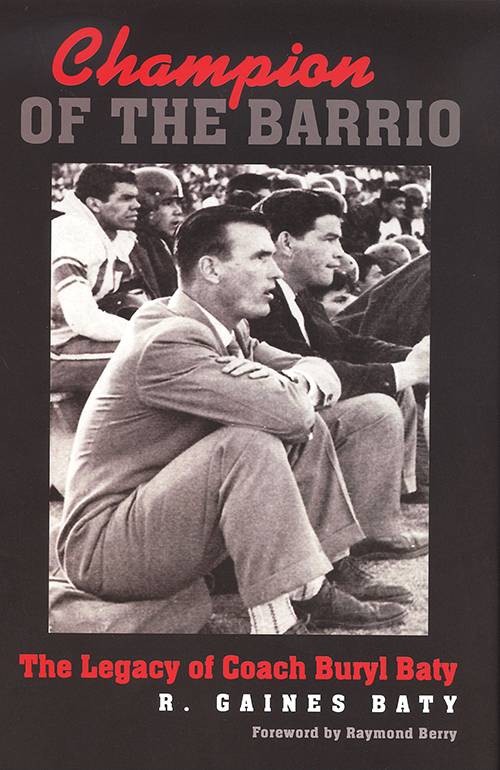

Champion of the Barrio: The Legacy of Coach Buryl Baty

by R. Gaines Baty

College Station:Texas A&M University Press, 2015

288pp. $24.95 cloth

Reviewed by

Joseph McDade

So who was this Buryl Baty? He was not the most successful Texas high school football coach of all time; that honor belongs to G. A. Moore, Jr., with his six state championships. Nor was Baty the most famous; surely that is Gary Gaines, the coach of Odessa Permian, who was chronicled in Buzz Bissinger’s Friday Night Lights. No: Buryl Baty coached for a relatively short time, won no state championships, and—despite his best efforts—did not win over the hearts and minds of those who hated his team for their Hispanic players. Even in his last year of coaching, it was routine for the team bus to roll into some small West Texas town and be greeted by signs reading “No dogs or Mexicans” in the front windows of diners and motels. His life seems tragically foreshortened, ended as it was by a horrific car crash on a Texas highway in 1954. What Baty might have accomplished as a coach, had he lived to old age, can only be left to speculation. But Buryl Baty the man—this is the Baty that, in Champion of the Barrio: The Legacy of Coach Buryl Baty, we see in full.

For all Baty accomplished—starring at quarterback at Texas A&M, serving with distinction in World War II, marrying the prettiest girl from his high school in Paris, Texas—his most memorable achievements came as a football coach at Bowie High in El Paso. There, the city’s Mexican-American population, sending their children to Bowie, saw Baty not only whip a football team into a perennial division contender, but also demand that his players, and in fact all the students in his charge (he doubled as assistant principal) be accorded the same respect.

Often, history is forged by geography. El Paso’s distance from Texas’s other cities, its removal from almost anything smacking of the Deep South, allowed it to become a laboratory for racial progress long before the rest of the state. (How isolated is El Paso? It is closer to San Diego than Houston.) It was Don Haskins’s Texas Western University (now University of Texas-El Paso) basketball team whose all-black starting five beat Kentucky’s all-white starting five in the 1966 Final Four championship game. And it was at Bowie High in El Paso that Buryl Baty would fight his own battles for equal rights—battles not as famous as Haskins’s, but just as significant for those he affected, and for those who witnessed what he did.

In the opening chapter the Bowie Bears are in Snyder, a town notorious for some of the worst and most racist fans in Texas. The team has already been refused lodging at one motel and has settled for one slightly out of town. It is time for the pre-game meal. The team bus rolls back into Snyder and parks in front of a diner. Coach Baty walks into the café, steps back out, and waits by the front door. A huge man wearing a white, food-spattered apron soon follows him and after a short, hushed conversation bursts out with, “Coach, them Meskins are not going inside my place of bui’ness!”

Coach Baty leans toward the massive, sweaty café proprietor and glares. “Yes, they are. I made reservations here, and we are gonna eat here. If you don’t feed my boys, we are gonna get back in that bus and head back to El Paso. And if we do, there’ll be no football game tonight.”

The owner blinks. The boys get their lunch.

Belatedly we arrive at our narrator. R. Gaines Baty introduces himself as his subject’s elder son in the preface and then disappears so thoroughly that many readers will have to be reminded in the epilogue that the four year-old boy his mother brought to football practice would grow up to be the handsome, wide-shouldered man grinning out from the book jacket. If Gaines Baty sometimes indulges in hagiography, his facts fit his tone. Buryl Baty did grow up in small-town Paris, and he played high school ball for legendary Mark Raymond Berry (father of Raymond Berry, who worshipped the older Buryl, then grew up and went to the NFL Hall of Fame along with teammate Johnny Unitas). He was a quarterback for A&M, and did go to war. As a coach, and with no prompting from anyone, he demanded simple human decency (often, no more than a hot meal) for players with last names such as Gonzales, Mendoza, and Olivas.

There is another element to this fine book: a peek at time long passed, when the football coach could enforce a curfew more rigorous than his own players’ parents’, when star running backs could be humbled by multiple swats from the head coach’s “Board of Education” for non-football infractions (such as mouthing off to a teacher), and when a local sportswriter might refer to the Bowie Bears as the “Bruins,” just to mix it up. (Ray Sanchez’s coverage of the Bears, excerpted generously by Gaines Baty, is a marvel of 1950s journalistic patois.) That era is gone, even where we might think it isn’t: today, Odessa residents will tell you that the Permian Panthers become life and death only when oil drops below thirty dollars a barrel and the townsfolk need something to hang onto.

Buryl Baty died at the age of thirty, and that is a shame. But with his name on the Bowie High football stadium (along with that of Jerry Simmang, an assistant coach who died in the same accident), his legacy is secure. This book adds to the legend.

Joseph McDade is a professor of composition and American Literature of English at Houston Community College. He also lectures on English Composition at the University of Houston.