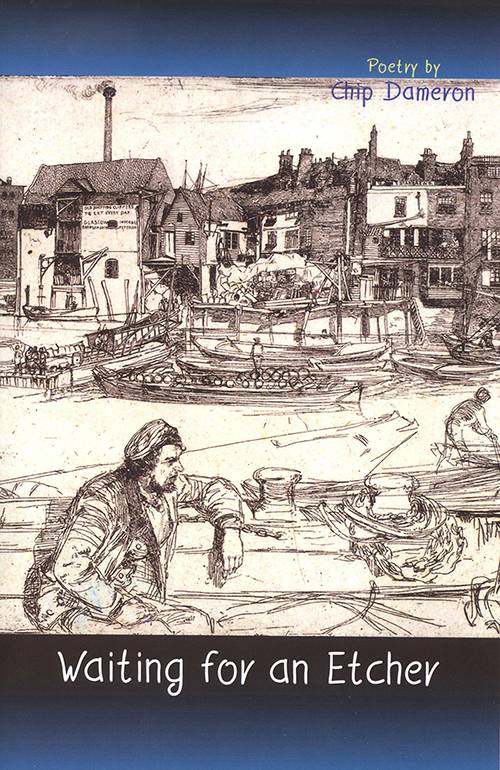

Waiting for an Etcher

by Chip Dameron

Beaumont: Lamar University Press, 2015

112pp. $15.00 cloth

Reviewed by

Dorothy Lawrenson

"One can only admire Dameron’s aspiration to forge original poetry from such iconic locations. Conversely, and somewhat more convincingly, certain poems describe places seen for the first time, but rendered familiar through skillful observation of specific details."

Writers have frequently observed that foreign travel teaches a paradoxical truth. In the words of G. K. Chesterton, “The whole object of travel is not to set foot on foreign land; it is at last to set foot on one’s own country as a foreign land.” Ultimately the traveler learns not just to see his home with new eyes, but also to understand himself better as well.

This must be a familiar lesson to a poet as well-traveled as Chip Dameron, whose collection Waiting for an Etcher seems to play out this realization. “Across the river is another version of your life,” begins the first poem (“Across”), immediately drawing attention to the proximity of Dameron’s Brownsville home to Matamoros, Mexico—but it also hints at the seductive and adventurous “other life” that hypothetically exists for the reader who decides to cross the river, board a plane, or book passage on an ocean liner. In this new, alternative life:

A man drinking coffee in a corner café

has been waiting, still waits, for you

to open the door and say what you

have often felt the need to say,

however halting and inexact it may be.

Dameron is keenly aware of the stark contrast between the Texan and Mexican sides of the border. “El Calaboz: Fences and Neighbors,” a poem concerning the construction of the border fence, riffs on Robert Frost’s “Mending Wall.” Here, as in other poems, the free flight of birds is contrasted with the divisive behavior of humans:

Early morning, small birds cross

the river from mesquite to mesquite,

singing the day awake. A hawk

drops to the top rail and commands

silence across this failed dichotomy.

Most of the other poems in the collection concern the experience of travel along the Texas border and within the U.S. and Europe. Themes of grief and loss, however, are also explored, but with the poet’s memories of family and friends grounded in specific places.

His taut treatment of the natural, the human, and the political within his local environment is where Dameron’s short poems are at their most effective. When he starts to roam further abroad he sometimes loses this sense of restraint as his poems become travelogues of various countries and cities. The aptly titled “Rambling Stories,” for example, takes place in Ireland, Greece, Turkey, and Mexico in a little over thirty lines. Far more memorable are the haiku-like poems in the section “Postcards.” Here, in its entirety, is “In Sligo”:

I’ve come here to

remember Yeats

and spotted a poem

on the Garavogue

a mute swan

carving blue sounds.

This poem, in asserting the importance of direct observation rather than literary allusion, highlights another potential pitfall for the tourist of famous and especially of literary cities; here, Dameron must first acknowledge before he can put to one side the shade of Yeats. Similarly, he name-drops Joyce in Dublin, Brunelleschi in Florence, and Hitler in Munich. In Paris (“Giacometti Park”), he treads a fine line between irony—watching “youths / pretending to play boules”—and cliché, as he confesses to being “absorbed by the city / of lights, still in love.”

One can only admire Dameron’s aspiration to forge original poetry from such iconic locations. Conversely, and somewhat more convincingly, certain poems describe places seen for the first time, but rendered familiar through skillful observation of specific details. “Hot Night Tale in Little Rock” is one such poem, recounting how the narrator and his companions decided to abscond from a conference to go to the Texas League ball game taking place across the street, “and cheered on the home team // as if we knew the shortstop’s / shortcomings, the pitcher’s best / pitch [. . .]” Although the city is not his own, he feels at home at the ballgame because he identifies so strongly with its familiar narrative:

the story we’ve known

by heart since we were kids,

sitting in the stands with our dads,

damp with humid hope, willing

for the game to go on as long

as it took to come to the right ending.

"Visit to Wolf House,” describes a trip to see the “glorious ruin” of Jack London’s California mansion. The first half of the poem sets the scene—the overgrown pool, the “stones stacked / around imagined rooms”—but the narrator soon realizes that “the real story of the walk” is the woman he sees coming down the hill with her family, “grinning in the sunlight,” determined to finish the journey to the house with the aid of her walking stick, “her palsy no bar / to her joy and the day of her joy.”

It is this attention to “the real story”—the human story, set against which most “travel” poetry becomes so much background scenery—that draws Dameron’s work ultimately towards richer explorations of loss and grief. In “Aftershock,” he inhabits “the gorgeous landscape / of the heart,” where “there is no sound / that can astonish like that absent / echo.” In this landscape,

I know as much as I can

ever know, the view almost familiar,

but who can put a finger on the thing

that changes everything [...]?

In seeking to navigate this emotional landscape, Dameron returns to his opening impetus to write the version of life “across the river.” But like a traveler returning from abroad, his literal, literary and emotional journeys have given him new eyes to see this unfamiliar and yet familiar country.

Dorothy Lawrenson is a graduate student at Texas State University.