Gassed Up in Houston

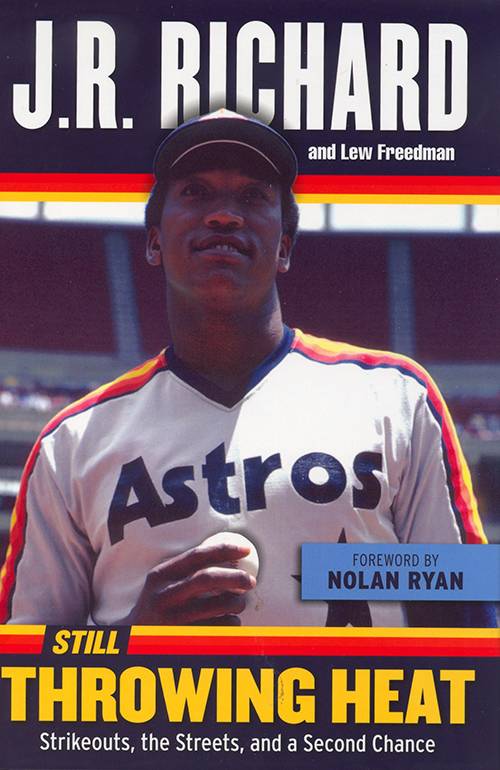

Still Throwing Heat: Strikeouts, the Streets, and a Second Chance

by J.R. Richard and Lew Freedman

Chicago: Triumph Books, 2015

256 pp. $25.95 cloth

Reviewed by

James Wright

From 1976 to 1980, J.R. Richard averaged nearly nineteen wins a year as a pitcher for the Houston Astros, including a twenty-win season in 1976. With a blistering fastball that regularly pushed 100 miles per hour, he struck out 1,163 batters over that same period, including two seasons (1978 and 1979) of 300-plus strikeouts. That same period saw Richard average an ERA (earned run average) of 2.98, including a league-best 2.71 ERA in 1979. He also racked up 1,239 innings and sixty-six complete games over that stretch, for an average of 275.2 innings pitched and nearly fifteen complete games a year, proving himself a workhorse of the league. Richard, without question, was one of the most dominant pitchers in baseball. As he walked off the mound at Dodger Stadium on July 8, 1980, after two scoreless innings as the National League’s starting pitcher in the All-Star Game, the thirty year old Richard had every reason to believe that his dominance would extend well into the future. However, those two scoreless innings would be his last in professional baseball.

Less than a month after his All-Star game appearance, while playing light catch in the Astrodome, Richard experienced a sudden and irrevocable medical emergency. Arm fatigue had landed Richard on the twenty-one day disabled list a week after the All-Star game. A battery of medical tests turned up a blood clot in Richard’s right shoulder. Not overly concerned about the blockage, doctors recommended a period of limited activities. The clot in Richard’s pitching arm turned out to be much more serious than diagnosed, and on July 30, Richard suffered a devastating stroke that permanently disabled the left side of his body. Despite a four-year rehabilitation effort to regain his form, Richard would never pitch again at anything resembling full strength.

With the help of veteran sports biographer Lew Freedman, J.R. Richard tells the story of his assiduous ascent and ill-fated fall in the unforgiving world of professional baseball in Still Throwing Heat: Strikeouts, the Streets, and a Second Chance. The book covers a broad outline of Richard’s life—from the genesis of his prodigious athletic talent to the peak of his career with the Astros to his too-soon departure from baseball to his recovery from his prolonged period of post-baseball tribulation. Though the book suffers from a tedious split-voice structure that divides the chapters between Freedman’s journalistic overviews and Richard’s conversational first-person narrations of identical material, Still Throwing Heat provides captivating insight into the strange forked-path that directed Richard’s life during and after his baseball career.

James Rodney Richard was born on March 7, 1950, in Vienna, Louisiana, “a tiny town of several hundred people in the north central portion of the state.” After a childhood spent fishing, shooting, and “develop[ing] [his] arm” by throwing rocks “at birds or rabbits,” Richard became a three-sport star at Lincoln High School in Ruston, Louisiana. The Houston Astros selected the 6’8”, 220-pound baseball wunderkind out of high school with the second overall pick of the 1969 draft. Richard made his debut with the Astros on September 5, 1971, against the San Francisco Giants, earning the win and striking out Willie Mays three times in the process (Richard notes that Mays reproached him after his third strikeout, saying: “ ‘My number is 24. Do you know who wears this number? Do you know who I am? You’ve got to respect this number.’ ”). Richard spent most of the next three seasons in the minors, but after his first full season with the Astros in 1975, Richard would have his way with major-league batters until that unfortunate mid-summer day in 1980.

Although Still Throwing Heat provides generous coverage of Richard’s professional and personal triumphs and tragedies, at the center of the book is the seemingly unaccountable medical ailment that felled such a flourishing and powerful athlete. The source of blame for the stroke is clearly a bone of contention for Richard. Richard vacillates between blaming the stroke on his physical prowess, in concert with the hyper-masculine sports code that calls for playing through pain, and on Houston’s apparent disinterest in safeguarding his ascendant talent. Richard speaks of a doctor telling him that “[he] was such a powerful pitcher that the muscles in [his] right shoulder had overdeveloped and were pressing against the ribs every time [he] threw . . . caus[ing] an irritation, a blockage,” at one moment, and at another of the Astros “not send[ing] [him] to a doctor right away” after his initial complaints of possible injury, a contention that Richard and his friend and former teammate Enos Cabell link to racial dimensions. While Richard may have come to terms with his feelings about being victimized by his own body, the purported acrimonious relationship between Richard and the Astros shows up from time to time in his account until the very end.

J.R. Richard pitched his last professional game “for the Daytona Beach Astros in rookie ball in 1983.” The Houston Astros released Richard in the spring of 1984. Understandably unmoored in the years following his stroke, Richard writes with stalwart frankness of his refusal “to acknowledge what the stroke had done to [him]” as he labored through year after year of modestly effective rehabilitation assignments; of anger and disappointment at being “cheated out of [his] baseball career”; of profound depression; of chronic unemployment; of the desperation that led to several months of homelessness in the mid-1990s. Eventually, with the help of friends and former colleagues, an MLB assistance fund, his current wife Lula, and his rekindled religious faith, Richard surmounted his problems and forged a stouthearted post-baseball identity for himself. And after being inducted into the Astros Walk of Fame in 2012, Richard’s feelings toward the Astros have softened to the point where he even attends the occasional game at Minute Maid Park.

James Wright is Houston regional editor for Texas Books in Review. He teaches composition and literature at Houston Community College.