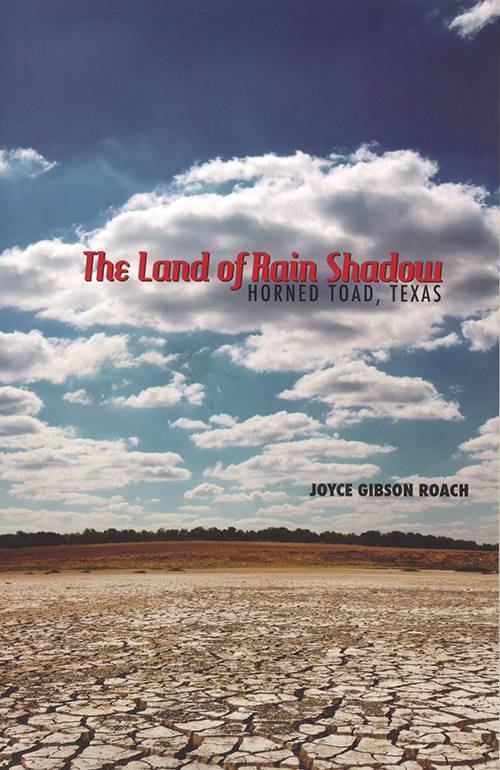

The Land of Rain Shadow:

Horned Toad, Texas

by Joyce Gibson Roach

Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 2015

113pp. $24.95 paper

Reviewed by

Jaye Dozier

"The most interesting parts of the collection are the variety of characters in Horned Toad, Texas. The most unfortunate parts about this collection, ironically, are the characters of Horned Toad, Texas. "

In her new collection of short stories, The Land of Rain Shadow, Joyce Gibson Roach seeks to immortalize the place that ignited her love for West Texas. Although not a direct representation of her beloved hometown, Roach explains that the fictional Horned Toad is meant to embody any small West Texas town characterized by people as stubborn and resilient as the arid landscape they occupy. Her collection serves as a kind of love letter to the pocket of Texas that she feels is seeped in “myth, legend, story, and song, and even when the body feels the worst of the place, wonder and imagination cannot be denied.” Although many would agree West Texas has its own brand of beauty, Roach takes on the daunting task of convincing her audience that it is more magical than dry.

The most interesting parts of the collection are the variety of characters in Horned Toad, Texas. The most unfortunate parts about this collection, ironically, are the characters of Horned Toad, Texas. These eight stories cover an extended period of time and portray people who not only “have their crosses to bear and gospels to proclaim,” but are various mixtures of “saints and sons-a-bitches.” The eccentric, stubborn characters sometimes feel more like caricatures than real people.

The first story of the collection, “In Broad Daylight,” is set in 1975 and told from the perspective of a nameless townsperson who observes and participates in a political rally held to overthrow the only candidate running for sheriff. The “women folk” of the town and their men are furious at the candidate for proclaiming that his first and only role in office will be to make sure every woman wears a bra, as rumors of the bra-burning feminist protest in Chicago have made their way to Texas. Not only does the narrator speak with a distracting drawl, he readily admits that the ketchup-smearing, greasy-fingered regular at the local café was “the closest thing to an educated man we had,” simply because he had “an honest-to-God degree from somewhere and could talk Spanish real good.” Having grown up in West Texas myself, I understand the kind of character she is trying to portray. Many people, especially those who choose to live far from stoplights and public buildings, can certainly speak with a drawl and prefer a more simple way of life. I believe it is a fault, however, to make them sound altogether uneducated. Although the narrator’s character may be found in small towns around Texas, Roach seems to aim more for stereotype than verisimilitude. It is much easier to look past the strange accent and poor grammar of someone in person than it is on the page, and Roach’s introductory narrator sets a rather unflattering tone for the rest of the collection.

Luckily, there is more to this collection. The book’s best story is “The Day After Pearl Harbor,” where the narrator documents her sisters attempts to join the war effort. The day after Pearl Harbor was bombed, the narrator describes how her sister Ada questioned whether to go through with the perm she had scheduled. She speaks mostly to herself in a kind of pep talk, saying, “It’s the decent thing to do, and I will do my duty by just keeping right on with regular activities of the town and our home. Isn’t that right? Aren’t I doing right?” Here, Roach artfully blurs the lines between vanity and patriotism. By making herself look better, Ada believes she is benefitting the war effort by pretending life is business as usual. This turns out to be a dangerous assumption, however, as her hairdresser accidentally left her client’s curlers on too long, burning off half of her hair. Although the story feels a bit stretched out, the tone is lighthearted with hints of darker symbolism that add refreshing dimension.

The final story of the collection, “Crucero,” is about a young black couple who travel to Horned Toad in search of work and shelter sometime after the Emancipation. Both of their children tragically die on the journey, and they eventually settle outside of the town at a place called Crucero, or “crossroads,” where they find work and a new home. There are a few standout moments, such as when the main character sings a eulogy for her lost daughter. Roach states that with each lyric, “the parched land that yielded only oil was watered and grew rich and green with pictures conjured by the black woman’s liquid voice.” However, although the narrator speaks with more eloquence, her story feels disconnected and ocassionally more like an interpretation of a history book than an authentic story.

Ultimately, Roach writes with real intimacy. Her love for the place and the people is on every page.

Jaye Dozier is a graduate student at Texas State University.